How Investors Analyze SBC and Why It Matters for Finance Leaders

Stock-based compensation (SBC) has become a pillar of corporate compensation strategy—and a focus of investor scrutiny. As companies continue to rely on equity awards to attract and retain top talent, the financial implications of SBC have become more pronounced. This is certainly true in sectors like technology and life sciences where SBC expenses represent a meaningful percentage of revenue. But even old-world sectors are grappling with unique talent attraction and growth goals.

Meanwhile, investors have become more sophisticated. They’re still concerned about dilution and plan design. But active (fundamental) investors are increasingly integrating SBC metrics into investment analyses, influencing both valuation models and capital allocation decisions.

For finance leaders, this evolution presents both a challenge and an opportunity. On the one hand, it can be hard to keep up with how different types of investors, particularly active fund managers, analyze SBC. On the other hand, understanding their hot buttons can help CFOs, CAOs, and finance teams proactively shape internal compensation strategies, engage more effectively with their boards, and lend more credibility to the company’s public disclosures.

This article explores how investors evaluate SBC, the metrics and frameworks they use, and the steps finance leaders can take to align internal decision-making with market expectations. We are also currently preparing a survey on how investors consume and evaluate reported SBC data. We invite you to share your thoughts with us at the end of this article.

Investors Have Had a Long Relationship with SBC

Insight into the evolving investor perspective can help finance leaders stay ahead of concerns and become more strategic in influencing compensation decisions.

A Look Through Recent History

2000s. Amid worries that mandatory option expensing under ASC 718 would spell the end of equity compensation (spoiler: it didn’t), investors debated whether SBC truly represented a financial statement cost.

2010s. The period following the rollout of Dodd-Frank executive compensation disclosure rules saw a rise in the influence of proxy advisors and passive institutional investors. These groups shifted the focus from the income statement to stewardship. They were concerned about core governance issues like say-on-pay, plan design, and pay-for-performance.

2020s. By this time, SBC expenses have grown dramatically. With average annual expense for large-cap companies at 2% of revenue (over 4% in the tech sector)—roughly five times higher than in 2006— the financial cost of SBC is back in the spotlight.

How much is too much? How much is too little? What trend is appropriate given top-line growth? Active investors (not to be confused with activists) are taking a front seat in parsing SBC data. As they do, they’re looking to CFOs and CAOs for more refined views on what an ideal level of SBC spend means for their organization.

Passive vs. Active Investors

Most finance teams are familiar with how passive investors, particularly the “Big Three” (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street), review proxy statements and evaluate equity plans with a governance-focused checklist. These investors care about dilution limits, plan design, and overall pay-for-performance alignment. Less explored, but perhaps more impactful for valuation, is how active investors incorporate SBC into fundamental investment analysis.

Making Sense of Ambiguity

Active fund managers allocate capital based on future returns, which means SBC can work for or against a company. As a strategic differentiator in the war for talent, SBC can fuel future growth. But excessive SBC can drag down earnings, distort operating margins, and create a wall of dilution that only exceptional growth can overcome. Investors might overlook high SBC in a bull market, but not when earnings quality and efficiency come under scrutiny.

Even the signaling of rising SBC costs can be ambiguous. Does it point to growth and investment, or a compensation model on the brink of collapse? Some research suggests that escalating compensation charges in R&D (as opposed to sales and marketing) are correlated with future returns.[1] Conversely, Zoom Communications made headlines in September 2024 when it publicly communicated it would introduce sharp cuts to its SBC program to rein in runaway dilution and cost. It turned out that Zoom had been too optimistic about growth, and the wall of dilution created by intense SBC granting had to be dismantled.

As market participants double down on fundamental analysis and the sustainability of earnings, they’re parsing SBC more finely than ever before.

How do Active Investors Judge SBC?

There’s no single way that active investors judge SBC. The approach varies from one fund to another. Even analysts within the same fund have their own methods for determining whether a company’s equity compensation program is responsible, excessive, or even advantageous.

Common SBC Metrics

Here are some key measures investors use to evaluate SBC.

SBC as a percentage of revenue or operating income

This is a common ratio-based approach to normalizing SBC by company size and performance. For example, a mature software firm might benchmark its SBC at 10% of revenue, whereas a leaner peer runs at 5%. Wide deviations raise questions.

Dilution metrics

Investors closely track dilution over time. Three metrics often cited are:

- Annual run rate (the annualized impact of new equity grants on total shares outstanding)

- Overhang (total unvested/unexercised equity as a percentage of outstanding shares)

- Burn rate (shares granted in a year relative to shares outstanding)

These metrics indicate how quickly shareholder ownership is being diluted by employee equity programs.

Trending and efficiency

Perhaps most fundamentally, investors analyze SBC trends over multiple periods. Is the company becoming more efficient with equity (granting less SBC as it scales), or is SBC growing faster than revenue? A high SBC expense or dilution might be tolerated if it’s in line with sector peers, but outliers will raise red flags.

SBC Feedback Loops

One analytical challenge is the feedback loop between SBC and stock price performance. As a company’s share price rises, each equity grant delivers more value, allowing fewer shares to achieve the same compensation. That makes SBC look more efficient. When the share price falls, however, a company must grant more shares to offer equivalent value, driving SBC expense and dilution higher just when performance has weakened. Offsetting forces exist (e.g., headcount growth during boom times versus higher forfeitures during busts), but these dynamics complicate forecasting. Finance teams and investors alike must account for these feedback loops to avoid surprises in SBC trends.

Management’s Narrative

Investors also pay attention to what management says about SBC.

- Is SBC framed as a strategic investment in talent (with expected returns in innovation or growth), or is it simply reported as an expense with little explanation?

- Do earnings calls and investor presentations discuss equity usage and dilution proactively?

- Is there a stated long-term target for SBC as a percentage of revenue or some “North Star” metric that the company is managing toward?

When companies are transparent about their equity strategy (like saying SBC as a percentage of revenue will gradually decline as the business matures), it can help set investor expectations and reduce uncertainty.

SBC Incorporation in Valuation

Importantly, active investors differ in when and how they incorporate SBC into their decisions. Some may largely ignore SBC until it breaches certain thresholds—say, if SBC expense suddenly exceeds a set percentage of revenue or if dilution crosses a painful watermark—at which point it triggers deeper analysis. Others integrate SBC directly into their valuation models and forecasts from the start.

The latter group of investors might adjust their discounted cash flow models to treat SBC as a real economic cost, either by subtracting projected SBC from free cash flow or by increasing the share count to account for ongoing dilution (or both). This modeling choice can meaningfully impact valuation. Research shows that analysts who exclude SBC from their models tend to produce higher, perhaps even overly optimistic, price targets than those who treat SBC as an expense.[2]

In practice, sophisticated valuation approaches like those advocated by NYU’s Aswath Damodaran adjust for SBC by reducing cash flows (to reflect the cost of issuing equity) and/or increasing the share count (to reflect dilution). This produces a more conservative estimate of intrinsic value. However, some investors don’t explicitly model SBC in spreadsheets but still factor it into qualitative judgments—for example, using high SBC as a proxy for management’s discipline (or lack thereof) in cost management, or as a risk to future earnings per share growth.

Other nuances matter, too. If SBC expense is accelerating, many investors will look at the ratio of SBC to employee count or the mix of SBC between the proxy NEOs and everyone else. They may try to understand whether stock options and performance-based awards are burdening earnings but unlikely to ever pay out.

Implications for Finance Leaders

The key insight for finance leaders is that investor perceptions of SBC can be influenced through data and disclosure. This is because investors don’t share a homogenous view on how to reward or punish companies for SBC usage. So it’s possible to boost SBC usage without facing stock price consequences, or conservatively hold SBC usage low without reaping any benefit from it.

Finance teams, in partnership with investor relations, have an opportunity to shape the narrative by highlighting the right metrics, providing context, and engaging on the topic. Moreover, investors increasingly expect finance executives to proactively understand and seek out their viewpoints on equity usage. A CFO or CAO who can discuss SBC in the language investors use will be better positioned to address concerns proactively and interact with the CEO, CHRO, and compensation committee as a true business partner.

Equity Budget Setting Requires a Common Language Between Finance and HR

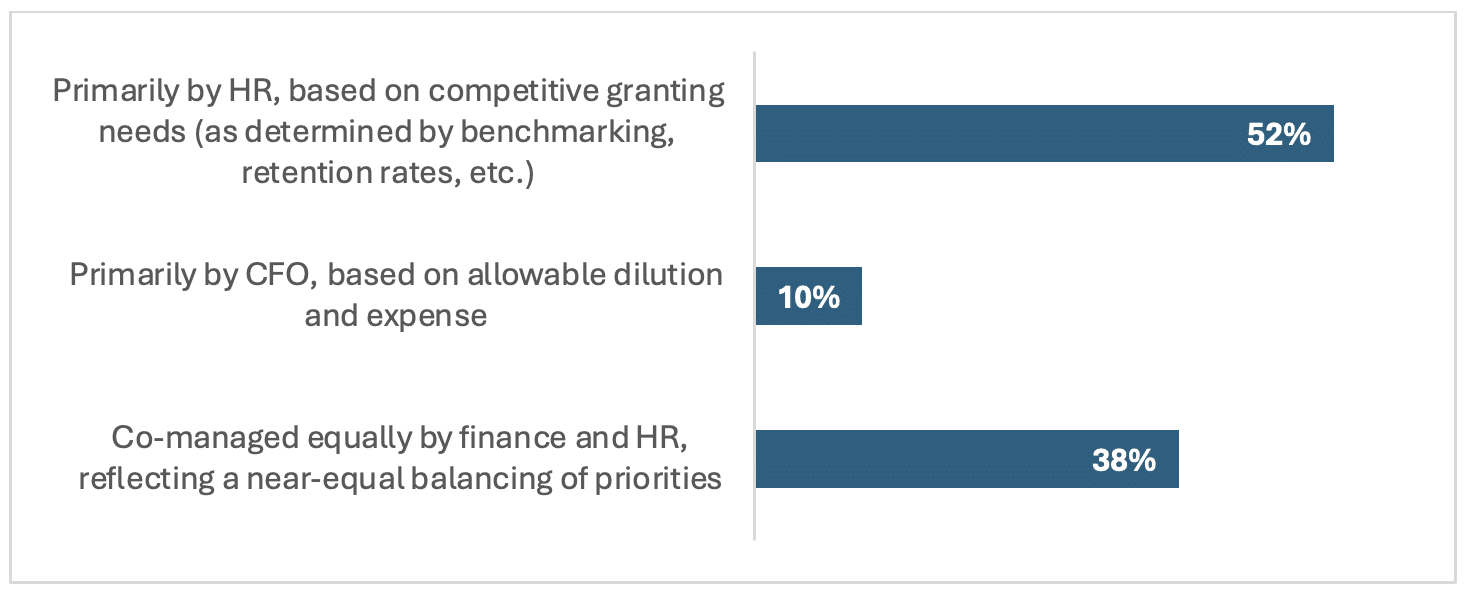

Based on our observations and industry surveying, there’s no universal practice for how companies set their annual equity grant budgets. At some companies, budgets are strictly tied to external market data, and HR takes the lead. Others fix the budget as a percentage of revenue or operating budget, and the CFO is in charge. Then there are those whose budgets are the result of negotiations between finance and HR each cycle.

This variability often leads to tension between HR and finance. Consider two real-life examples drawn from recent experience.

Company A (high-growth, “talent-first” strategy). During a period of rapid growth, Company A generously awarded equity, believing strongly in a talent-first approach. For years, HR largely drove equity grant decisions as the company hit one ambitious growth metric after another. However, when growth began to slow and margins tightened, the CEO and CFO—under board direction—instructed HR to cut the annual equity spend by 33%. The organization went through a painful adjustment as years of a permissive equity culture had to be unwound virtually overnight.

Company B (evolving business model). Company B was expanding from a traditional brick-and-mortar model into digital services. To compete for top tech and digital talent, the company had to increase its equity compensation offerings far beyond historical norms. The CFO grew alarmed by the size of that increase—and by the inconsistent grant practices that developed between the legacy business unit and the new digital unit. Tensions quickly arose as the CHRO pushed to pay whatever it took to hire key talent. The CEO found herself mediating the conflict.

These cases show how the lack of a shared finance-HR perspective on SBC can lead to a whipsaw effect—first swinging too far in one direction, then abruptly snapping back. The results include inconsistent decision-making, loss of credibility with employees and the board, and a degradation of the perceived value of the equity awards.

Our advice to CFOs and CAOs is to lead from the front on this issue. There are objective market benchmarks (peer grant practices, burn rates, etc.) that should inform the opening bid for how much equity to allocate. From there, finance can stress test the proposed equity budget against financial constraints and investor expectations. Throughout these processes, any disconnects with HR should be addressed quickly before small problems turn into big ones.

In practice, we find that once core compliance with SBC accounting (ASC 718) is handled, the finance team’s charter can evolve into developing dashboards, trend analyses, and “flux” reports that illuminate SBC usage in a more strategic context. For example, at Equity Methods we often help clients move beyond basic reporting to build internal SBC dashboards. These might track run-rate dilution against peer benchmarks, forecast the impact of various grant sizes on future EPS, or model how long the current share reserve will last under different hiring plans.

Armed with such analytics, finance leaders can engage in more productive dialogue with HR and the compensation committee. By bringing an investor’s perspective to internal decision-making, finance can copilot the equity strategy rather than react to equity spend after the fact.

Where Else Can Finance Influence the SBC Narrative?

Besides budgeting, these are some other areas where a proactive finance leader can help tell a better equity story to the market and potentially avoid negative surprises.

Dilution Management Through Share Buybacks

Share buybacks can be an effective tool to neutralize dilution from SBC grants, but they must be wielded carefully. A poorly timed or purely reactive buyback (one that appears solely aimed at offsetting excessive equity issuance) may look to investors like management is just trying to cover up SBC dilution.

Finance should evaluate buyback decisions through a rigorous capital allocation lens. Are buybacks the best use of cash relative to investing in growth, M&A, or paying down debt? And if buybacks are pursued, are they sustainable given the projected SBC trend? Modeling different dilution scenarios can help the team plan buybacks such that they meaningfully offset dilution without draining resources from higher-value uses.

It’s also important to communicate clearly. Investors appreciate knowing how buybacks fit into the broader capital return strategy and how those buybacks relate specifically to equity compensation. Transparency here helps investors separate short-term dilution optics from long-term value creation. Keep in mind that using buybacks to offset SBC effectively turns what was a non-cash expense into an actual cash outlay. Companies shouldn’t claim the benefit of adding back SBC to earnings without also acknowledging the cost of buying back shares needed to prevent dilution.

In short, buybacks can bolster an equity story, but only if they’re part of a thoughtful, economically sound plan.

Share Reserve Forecasting

Most companies ask shareholders to re-up their equity plan pools every three to five years. HR typically owns the process of when to go back to shareholders for more shares, but finance has an important seat at that table.

Notably, proxy advisors have been pushing companies to seek share authorizations more frequently in smaller chunks, rather than large infrequent requests, to avoid excessive future dilution. Finance should form a point of view on how the frequency and size of share reserve requests might affect investor perception. For instance, waiting too long and then requesting a massive increase can alarm investors (raising questions about why equity use wasn’t managed more conservatively), whereas very frequent requests could signal aggressive equity use each year. By planning the optimal timing for authorizations, finance can help the company maintain its credibility with shareholders.

Disclosure Strategy

With ASU 2024-03 coming into effect, companies will be disaggregating compensation costs in more detail in their income statements. This offers the chance to tell a more transparent, informative story about compensation in the MD&A, footnotes, and investor communications. At the same time, more granular disclosure hands investors a magnifying glass, enabling very nuanced questions.

Finance will need to decide how much to voluntarily disclose about SBC beyond the minimum required, bearing in mind that the adage of “less is more” is increasingly risky in an age of transparency. Sparse disclosure can make investors wonder if the company has something to hide or, perhaps just as concerning, that management itself doesn’t have a good handle on the data.

Finance leaders should also be prepared to explain SBC trends and drivers in plain language. Suppose SBC spiked year over year. Was it due to one-off new hire grants for a big project, or broad market adjustments to keep up with competitors? A thoughtful disclosure can preempt investor skepticism and demonstrate that management is actively managing its equity spend.

Compensation Committee Briefings

The compensation committee relies on HR, but finance leaders often sit in the room. Bringing an investor-oriented perspective to these meetings can elevate the discussion. For instance, if a broad-based grant is proposed that spikes the SBC expense line, finance can explain whether it’s likely to trigger concern among investors or remain within acceptable boundaries.

Ultimately, finance teams can transform SBC from a reactive compliance burden into a proactive storytelling and strategy tool. As compensation committees formally and informally expand their charters to encompass broader human capital management topics, we anticipate more questions that delve beyond executive compensation and into the company’s overall strategy for SBC.

Help Shape the Dialogue—What Do You Want to Know from Investors?

As we prepare to launch an investor survey, we want to hear from you. What insights would help you better inform your company’s equity strategy, investor messaging, and compensation design?

Below are sample questions that finance leaders can answer to shape the survey’s design.

We invite you to contact us with your responses or additional questions you’d like to see addressed in the investor survey.

Wrap-Up

Stock-based compensation sits at the intersection of talent strategy, financial discipline, and investor perception. And yet, SBC is often managed in organizational silos: HR focuses on design and retention; legal on compliance; finance on accounting and forecasting. Few stakeholders have visibility into how investors are actually processing the data.

By better understanding how the market interprets SBC disclosures, finance leaders can:

- Support more informed equity design choices

- Build stronger partnerships with HR and the compensation committee

- Anticipate and proactively address investor concerns

- Improve the quality of proxy and 10-K disclosures

At Equity Methods, we believe finance has a unique vantage point to elevate the dialogue around SBC. We’re preparing to launch an investor survey to equip companies with the investor-side insights needed to sharpen strategy, drive alignment, and build trust.

Let us know what matters to you. Let’s shape the future of SBC disclosure and strategy together.

[1] Rajgopal et al., “Evaluating Nature of Expense Classifications: Evidence from Labor Costs,” working paper, October 2024.

[2] Mohanram, P. S., White, B. J., & Zhao, W. (2020). Stock based Compensation, Financial Analysts, and Equity Overvaluation. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(5), 1040–1077.