Convertible Securities: Do “Greater-Of” Inputs Threaten Equity Classification?

Stock warrants and other convertible securities often include a provision that protects the holder by spelling out what happens to the warrant should there be a change of control. Such provisions often state that the warrant will settle at the Black-Scholes value upon a change of control, and specify how the inputs for the Black Scholes calculation should be derived.

Sometimes, a change of control provision will include “greater-of” inputs, meaning the holder gets the greater of two or more values upon payout. For example, the holder might receive a fixed volatility (like 100%) or a historical volatility, whichever is greater. Or they might receive the greater of multiple share price dates.

This raises a tricky question. ASC 815-40 says that to classify a financial instrument as equity, it must, among other things, be considered indexed to the entity’s own stock. Last December, at the annual AICPA & CIMA Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments, the SEC’s Gaurav Hiranandani observed that the commission had been fielding inquiries from SEC registrants and their auditors on the application of the indexation criteria in ASC 815-40. For example, does a greater-of input “create leverage or introduce impermissible variable inputs that push the instrument into liability classification?”

SEC staff elected not to take a position on that issue, merely indicating that judgment is required based on a totality of the facts and circumstances. But the implication is that these features could disqualify the instrument from being indexed under step 2 of the indexation test even though the pricing inputs are technically part of Black‑Scholes. In the rest of this article, we’ll discuss the context of greater-of inputs along with considerations in gauging their impact.

Why These Terms Matter

Warrants and other derivative securities can lose significant value during a buyout because the assumptions that made them valuable change.

- Early cancellation. Sometimes the instrument is simply canceled when the buyout happens, causing the holder to lose both the remaining time to use it and the extra value it had because of future possibilities.

- Conversion into buyer’s stock. Other times, the warrant is converted into a right to buy the acquiring company’s stock. But the buyer is usually a larger, more diversified company. Bigger companies’ stocks typically have less leverage, so the warrant has less upside.

Even the rumor or announcement of a transaction can affect value given that warrants are sensitive to volatility. If the company is rumored to be a target, volatility may rise due to speculation, leaving more chance the warrant could profit. If a deal has been announced, volatility may drop since the stock’s price is set by the purchase price. Either way, the volatility may not accurately reflect the company fundamentals absent a transaction.

So to protect investors, it makes sense to include a payout that compensates the holder if a confirmed or rumored deal distorts the company’s stock price. Of course, it’s impossible to forecast the stock price, volatility, and remaining term in the future. However, warrants can be written to include the key terms along with caps, floors, and date ranges. These provisions help make the pricing fair and prevent problems caused by unusual stock behavior.

The Indexation Test in ASC 815-40

The indexation test under ASC 815‑40 is where adjustment provisions get scrutinized to decide whether a warrant can be accounted for as equity instead of a derivative liability. To be treated as equity, the warrant must pass the two‑step test to show its value is indexed to the entity’s own stock. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Examine exercise contingencies. Ask whether the right to exercise the warrant depends on market indices or events outside the issuer’s control (other than the issuer’s own stock or business metrics). If exercise depends on such external indices, that provision can bump it out of the indexation test.

Step 2: Review settlement terms. The settlement amount must also be one of the following:

- The difference between a fixed number of shares and a fixed monetary amount (i.e., fixed‑for‑fixed)

- An amount where the strike or share amount is variable, but the only inputs are those used in a standard option pricing model like Black‑Scholes (e.g., volatility, interest rates, term, dividends, etc.)

If either step fails, the instrument is classified as a liability and measured at fair value through earnings.

A clause that amplifies the return (settlement equaling 1.2 times the share price, for example) introduces leverage and creates a non‑linear payoff that changes the economics of the instrument. As a result, it falls outside what ASC 815‑40 permits because the payoff no longer tracks a fixed-for-fixed structure. Even minor leverage means the instrument fails the indexation test and must be accounted for as a liability. This follows from the principle that multiplier features represent extra variables beyond what a basic option pricing model allows.

Evaluating the Impact

In order to consider the various facts and circumstances, it’s important to understand the impact of different greater‑of terms.

Let’s walk through a couple of examples. Suppose we have a typical provision where:

- The risk-free interest rate and dividend yield are based on market inputs

- The strike price is based on the original instrument

We’ll assume the instrument is a warrant since warrants have fewer inputs than convertible bonds and it’s easier to see the changes.

Stock Price

When an acquisition is announced, the offer is usually above the market price. Over time, the target company’s stock price slowly moves toward the deal price. If another bidder enters the market, the stock can jump up. If problems arise with the deal, the stock can fall. But once the deal is done, the stock price lines up with the amount of money investors will get for each share.

A “better-of” or “best-of” price clause guarantees the investor will get the highest price available over a certain period, rather than just the final price at a specific date. If the stock price closes at the highest price over the period, however, a better-of or best-of price may not have any impact.

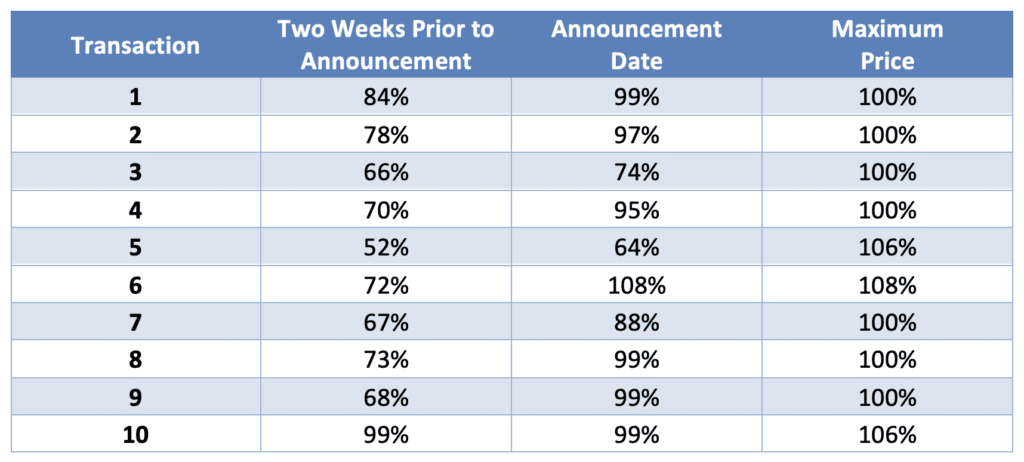

To look at this more closely, we look at 10 recent deals from Russell 2000 companies to see how much the stock price moved from the announcement date to the completion date, using the completion date price as 100%.

Overall, we see that most of the stock price movement usually occurs on the announcement date. Although the stock price climbs throughout the period, it exceeds the final price in only three of our 10 deals, and never by more than 10%. This makes sense, as our sample consists only of completed deals. Therefore, the only reason we would expect to see a price higher than the closing price is if there were rumors of a better offer that didn’t come to fruition.

In transaction 6, the announcement date price exceeds the closing price. The fact pattern here was unique as the acquisition price included a contingency based on the company’s future revenues. We would expect this to occur only in unique circumstances.

Practically, this means using a “best-of” price rather than the closing price will likely have little impact on the transaction, as the typical deal ends at the maximum price.

Volatility

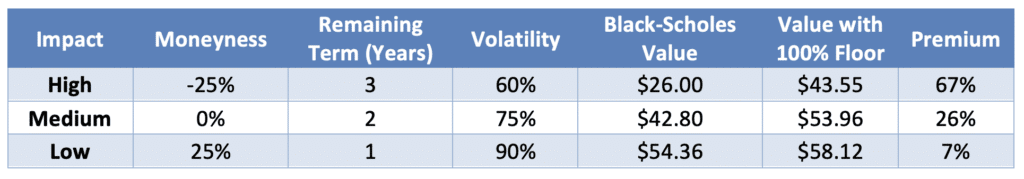

To illustrate the effect of a volatility floor, let’s consider a warrant provision that sets a 100% volatility floor for deals where the actual volatility is lower. We expect the provision will be most valuable under the following conditions:

- Low existing volatility. If the stock is usually calm, the impact of a floor will be higher

- Longer term. The more time there is before the warrant expires, the more time there is for the stock to move and the greater the impact of the difference in volatility

- Stock price below strike price. Out-of-the-money options benefit more from volatility than in-the-money ones, as this gives them more of an opportunity to rise in value and hit the strike price

Table 2 shows high, medium, and low-impact scenarios for a warrant with a $100 strike price, no dividend yield, and a 4% interest rate.

The result of this analysis is what we expect. The impact is potentially larger for warrants priced out of the money, with a longer term, or on companies expected to be more stable.

The takeaway is that while stock price doesn’t appear to impact the payment value, volatility certainly does. As our sample in Table 1 shows, volatilities of companies tend to be well below 100%. So this volatility floor may have a significant impact.

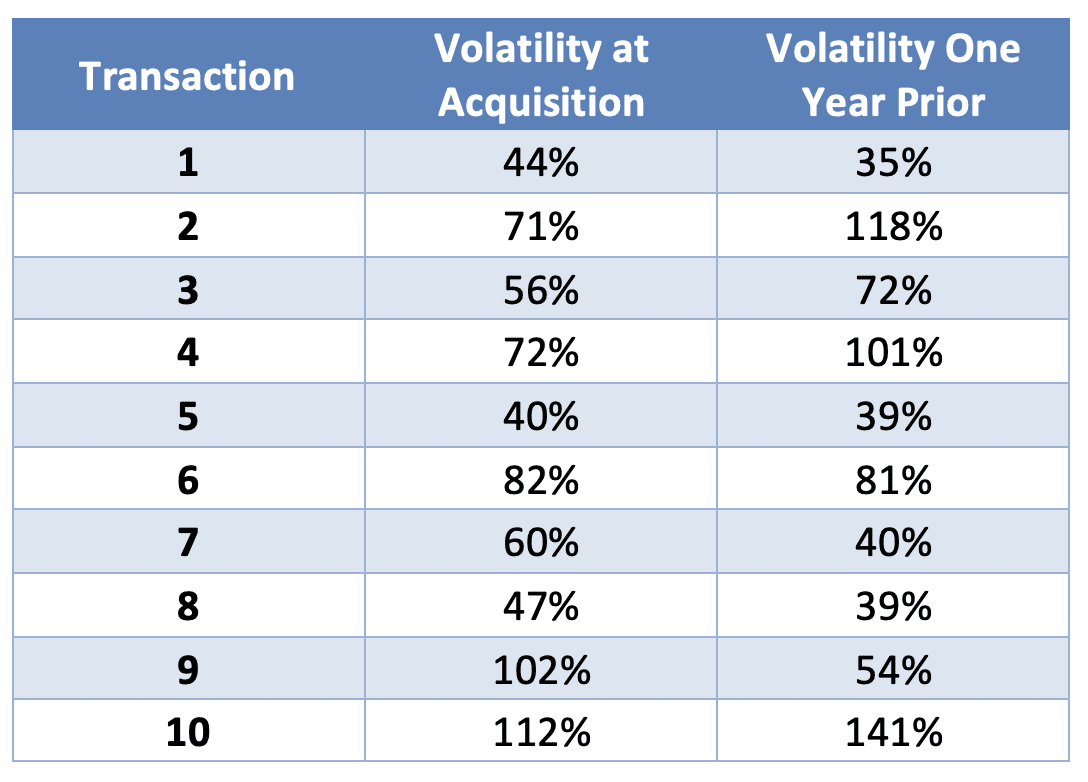

On the other hand, recall that in the time prior to a transaction, investors know the closing price and the stock may trade at a lower range. The implication is that the 90-day volatility may indeed be less than the expected volatility of the company had the transaction not occurred. Another look at our sample deals shows the potential impact here.

Interestingly, the trend is for lower volatility companies to have higher volatility prior to the transaction while high volatility companies tend to increase in volatility. This is consistent with the assumption that prior to a deal, trading is more focused on the likelihood of a deal getting done rather than the economic fundamentals.

Final Thoughts

Keep in mind that the SEC staff’s observations are context specific. Although the staff highlighted greater‑of inputs as features that require careful scrutiny under ASC 815‑40, they didn’t declare these provisions inherently disqualifying. Indeed, in a recent example, SEC staff explicitly permitted equity classification despite the presence of greater‑of volatility and stock price inputs. The reason was that they were individually acceptable valuation inputs and various sections of the codification permitted floors, caps, and average pricing inputs.

Our analysis of actual change-of-control deals indicates that stock prices rarely exceed the deal closing price during the pre‑close period, meaning a best‑of price floor often has minimal practical effect. This supports the view that a longer‑term average or greater-of share price input may be commercially reasonable (i.e., not a value‑enhancing lever), thus consistent with fixed‑for‑fixed or standard option input criteria.

On the flip side, our volatility floor analysis confirms pre-deal close market volatilities tend to be below assumed thresholds, so they can increase the valuation of a warrant. More importantly, our deal-based analysis shows that the impact of such floors often arises because actual pre-close volatilities are below the assumed threshold—a commercially reasonable behavior because investors know the closing price and the stock may trade at a lower range. This supports the view that a floor set at issuance could be considered an allowable, fixed model input (not an impermissible variable) under step 2 of the ASC 815‑40 indexation test.

Clearly there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. If you’re concerned about the classification, a careful review of the terms alongside your economics may be useful as you negotiate the transaction. As is so often the case, professional judgment—supported by documentation—is key.