7 Frequently Asked Questions on Option Exchange Program Design

The current economic climate has had a disparate and at times unpredictable impact on business. Unemployment remains low, and demand and spending remain high overall. But supply chain challenges, high inflation, and rising interest rates have created a challenging operating environment, causing many companies’ share prices to go down.

In times of broader stock market decline, one key equity compensation trend that tends to crop up is a spike in option exchange activity. It happened following the dot-com crash in the early 2000s and again in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. With options deeply underwater, companies offered option exchanges to restore the broken equity incentives.

Over the past decade-plus, we’ve maintained a proprietary, comprehensive database of option exchange tender offers filed with the SEC. In this article, we’ll share some of the key trends and best practices we see from the data and from our own experience shepherding clients through the option exchange process. If you find yourself considering an option exchange or may consider one in the future, read on.

#1. What is an option exchange?

An option exchange is an equity compensation program that allows employees to exchange their underwater stock options for a new award.

The purpose of an option exchange is to restore the retention and incentive value of outstanding awards. As options fall out of the money, the probability that they expire without any value rises. More importantly, the perceived value—how employees view the value of their awards, so what they believe they would lose by terminating prior to vest—falls. An option exchange drives retention by allowing employees to replace these low-retention, out-of-the-money options with new awards.

To implement an exchange, the company will have to make several key decisions. The rest of this article will outline what those decisions are, what companies have done in the past, and what things you should consider before making each decision.

#2. Should we seek shareholder approval?

Usually, shareholder approval is required to implement an option exchange program. Any option plan introduced after a company goes public is effectively required to prohibit repricings without shareholder approval. In addition, the NYSE and NASDAQ require that repricings get shareholder approval unless plan documents expressly permit them.

The main exception is for companies whose option plan was in place prior to going public. In such cases, repricings or exchanges may not strictly require shareholder approval, but companies in this situation may consider asking for shareholder approval anyway. (Note that all of our data in this article are from filed tender offers, therefore mostly from companies who sought shareholder approval.)

Major Considerations

Stock Plan Legal Permission. As we mentioned, some plans explicitly permit exchanges and repricings. But most don’t, meaning shareholder approval is required. If your plan isn’t clear, we recommend consulting with legal counsel to determine what’s allowed.

Shareholder Scrutiny. Opting to offer an option exchange without shareholder approval, even in cases where that’s legally permitted, will drive negative downstream consequences with shareholders. Proxy advisors like Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, as well as many institutional investors, have policies to vote negative on say-on-pay and vote against compensation committee members who approved the exchange.

#3. What type of exchange should we offer?

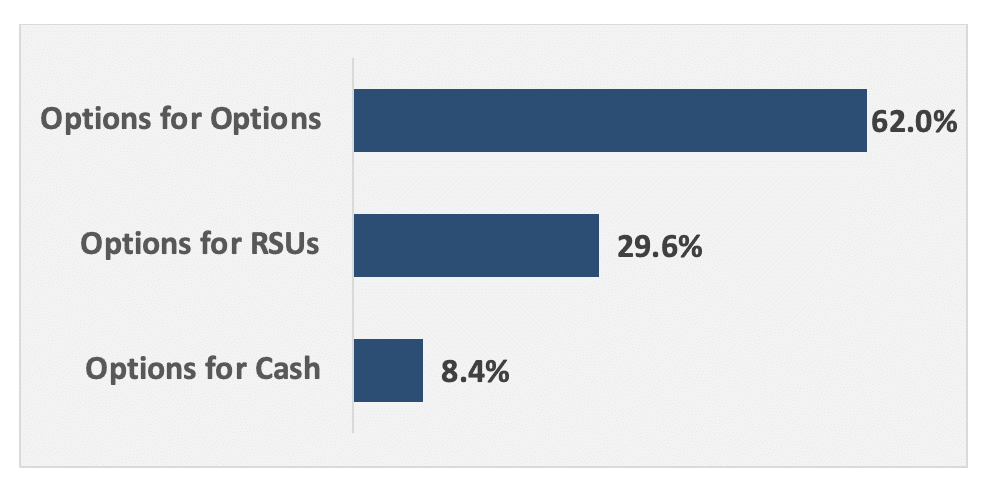

All option exchange programs involve employees giving up underwater options, but they may differ in what employees receive in return—new options, restricted stock units (RSUs), or cash. Exchanging for new options is most common, but far from universal.

Major Considerations

Compensation Strategy. While offering options in a like-for-like exchange is the most common, the best practice in our experience is to align the new instrument with future equity compensation strategy. If employees have soured on options and the company plans to move to full-value shares like RSUs or cashed-based incentive compensation, it may make sense to offer these types of awards instead.

Stock Plan Goals. Another critical equity compensation challenge that typically accompanies stock price decline is a depleted stock plan. Since option exchanges reduce the number of shares outstanding, they can be used as a tool to mitigate this concern as well.

If the goal is to maximize share pool impact or simplify the cap table, an options-for-cash exchange will return all exchanged shares to the stock plan at the cost of a cash outlay. Options-for-RSUs provide a middle ground where higher exchange ratios significantly reduce the number of units outstanding. Last, options-for-options provides the smallest share plan benefit among the three options, but can still have a sizable impact if options are deeply underwater and exchange ratios are high (i.e., many old options must be given up for a single new option—see question #4 below).

#4. How favorable should our exchange be to employees?

Most exchange programs involve a tradeoff: In exchange for getting rid of underwater options and replacing them with something more valuable, recipients typically get fewer of the replacement awards.

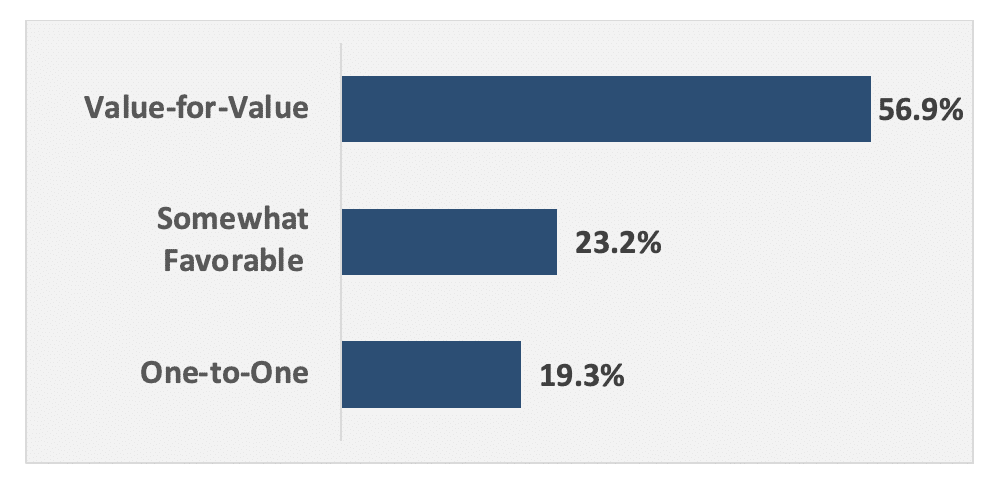

This isn’t always the case. At one end of the option exchange spectrum are one-to-one repricings where the strike price is decreased but the same number of units are held. Much more common is the other end of the spectrum, where many companies offer a value-for-value exchange that provides a lesser number of replacement awards such that the accounting fair value of the pre-exchange and post-exchange awards are equal. In between, some companies aim for a middle ground approach.

Major Considerations

Shareholder Scrutiny. Shareholders and shareholder advisors may view option exchanges as antithetic to the goals of equity compensation. By allowing for an exchange, companies de-link employee outcomes with shareholder outcomes.

A neutral, value-for-value exchange is relatively easier to justify to shareholders for a couple of reasons. First, it doesn’t provide pure excess value to employees but instead trades away upside for lower risk. Second, a value-for-value exchange reduces overhang and potential dilution by reducing the total number of outstanding options. More favorable, non-neutral exchange terms can be a tougher sell, but they’re still reasonably prevalent in the market because they can be more effective in driving retention. In our experience, shareholders will be more accepting of an employee-favorable exchange design if underperformance resulted from systemic or macroeconomic factors outside a company’s control, rather than company-specific underperformance.

Finally, to the extent that voting shares are privately held or controlled by a smaller group of insiders, companies can offer a more favorable exchange without needing to worry about shareholder pushback or negative say-on-pay outcomes.

Simplicity. One-to-one programs have a major, simplifying feature: A tender offer typically isn’t needed. They’re required for most exchange programs because there’s an investment choice that the employee needs to make on whether to give up some shares in exchange for the lower strike price, and the company cannot do this unilaterally. One-to-one programs make the holders better off if the only award term that changes is the lower strike price. Since holders are either the same or better off on every single dimension, a tender offer isn’t needed. This fact isn’t a driving force to adopt a one-to-one repricing, but it is a positive for companies that can run such a program with their shareholder and accounting cost constraints.

Retention Risk. While it’s important to preserve the link between share price performance and equity compensation outcomes, it’s also critical to guard against excess turnover of key personnel that can exacerbate stock price concerns. More favorable exchanges can more strongly mitigate this risk and may make business sense, even though they may be more heavily scrutinized by shareholders.

Accounting Cost. Option exchanges are considered an equity modification under ASC 718, and incremental expense must be recognized for any excess value created during the exchange. Should a company elect to offer a more favorable exchange, it will need to expense the incremental cost. Value-for-value exchanges, by construction, result in little to no incremental cost.

#5. Should top executives and board members be eligible?

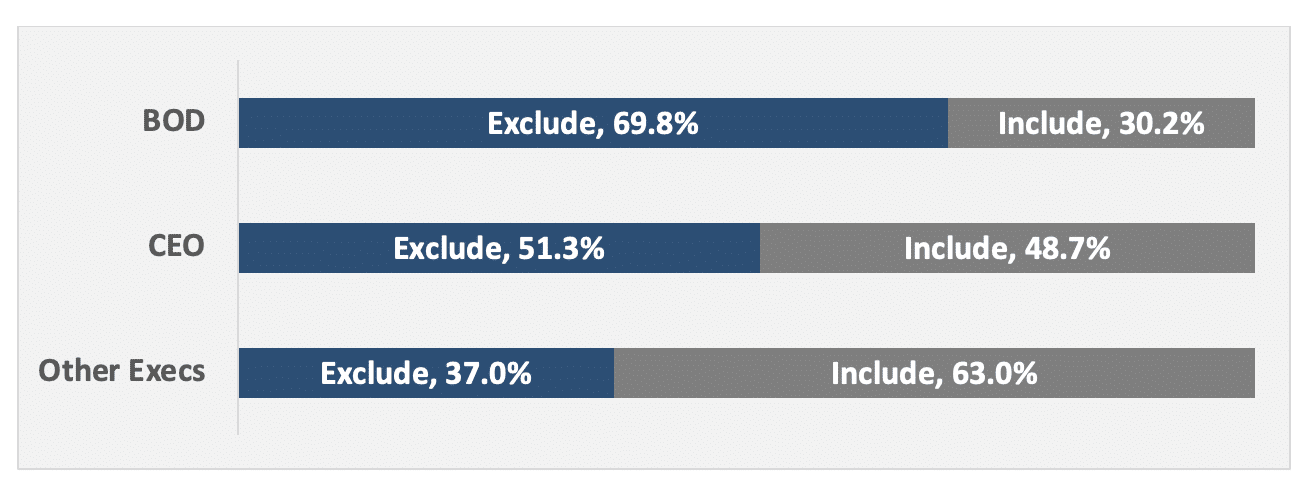

Companies may choose to exclude certain option holders from the exchange program. The rationale is that there should be increased accountability for top-level directors and employees who have a higher degree of control over company share price than lower-level employees. Around half of companies have historically excluded CEOs, with a greater portion excluding the board of directors and a smaller portion excluding all executives.

Major Considerations

Shareholder Scrutiny. Given the level of disclosure and scrutiny around executive compensation, the inclusion of directors and executives can create downstream say-on-pay and compensation committee voting concerns.

Additionally, ISS’ and Glass-Lewis’ criteria both explicitly state that executives and directors must be excluded in order to receive a positive vote recommendation. If substantial portions of shareholders follow their recommendations and/or there are pre-existing concerns from those advisory groups, then including executives and directors may be unrealistic for achieving shareholder approval.

Stock Plan Goals. For some companies, share recoupment for the stock plan is a driving or major consideration for the exchange program. In these cases, including more employees—and especially the executive team—may be crucial to this program goal as they tend to have a significant portion of the outstanding shares.

Circumstances of Exchange. The stronger the case that factors outside of company control drove the stock price decline, the stronger the argument to include the most senior employees. On the flip side, if peer companies and competitors’ share prices are performing well, shareholders may be more inclined to exclude top-level directors and employees.

Regardless of circumstance, the shareholder view is that they themselves aren’t given the opportunity to recoup lost value. Thus, many would argue that employee equity holders, especially directors and officers, should be subject to the same economic outcomes to align incentives.

Retention Risk. Often, the strongest argument in support of executive participation is to mitigate key personnel retention risk. Perceived fairness aside, higher senior turnover can amplify share price underperformance if those people are key to the company’s success. If executives are at high risk of leaving, allowing for their participation in an option exchange may be optimal, and companies may be able to alleviate shareholder concerns with direct investor engagement.

Other Design Decisions. As mentioned in the prior section, the favorability of the exchange program can also dictate whether it makes sense to include executives or board members. While shareholders get a yes-no vote to approve option exchange programs, executives and the board have a hand in designing them. Allowing the most senior employees to participate in a particularly favorable exchange that those same people helped design can create a negative shareholder perception. If the exchange is value-neutral, and the exchange is only offering an opportunity to alter the leverage profile of the award and not the total value, a stronger argument can be made to allow full participation.

#6. Should we alter vesting?

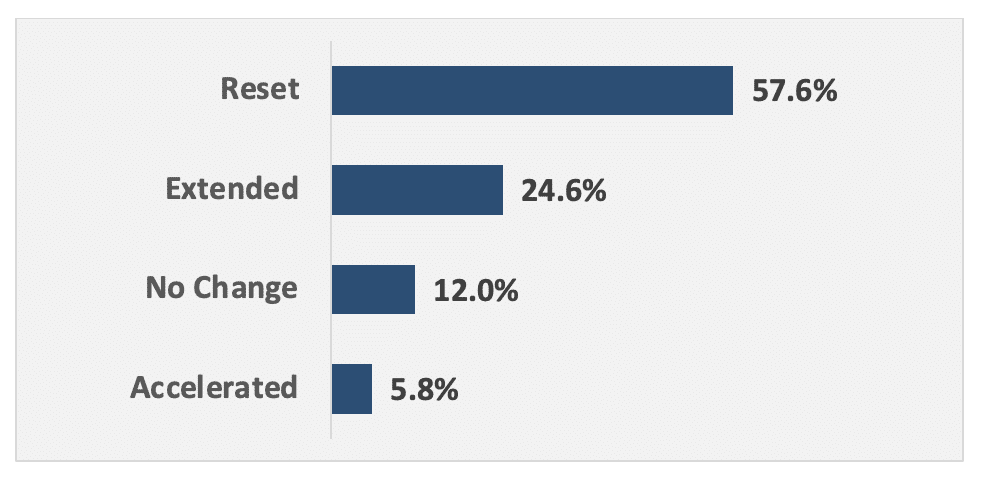

Most companies amend the vesting schedule when implementing an option exchange. The argument is that the new awards are more favorable to employees, so they come with strings attached in the form of longer vesting. The employee gets a new award they prefer overall, and the company gets greater retention benefit. There are a few variations on vesting treatment in practice:

- Reset—Vesting will start from scratch as if the new awards are an entirely new grant. This may be the same as the company’s new grant vesting schedule, or it may be a shorter, in-between schedule. In any event, all replacement awards get the same new vesting schedule. This is the most common treatment, albeit not an overwhelming majority

- Extended—Vesting dates will be pushed back by a fixed amount of time. For example, every vest date may occur one year after the original vest date. Already-vested shares typically require additional vesting as well, often at least equal to the length of the extension for other tranches

- No Change—Vesting will occur on the original vest schedule. This is most common when a company is trying to maximize the employee favorability of the exchange, and especially common when avoiding a tender offer with a unilateral repricing

- Accelerated—Vesting will occur in advance of the original vest schedule. This is most common with cash-out transactions where retention isn’t a goal at all

Major Considerations

Other Design Decisions. Extending or resetting vesting can be one of the easiest ways to support and justify other favorable exchange provisions. If the intent is to add value to employees’ equity via the exchange to facilitate retention, creating an explicit link between extended service and compensation is extremely common. Any employees who opt to forgo additional value due to a vest reset or extension may be signaling that they’re likely to leave regardless of the exchange.

Based on our data, there are small bumps to participation for more favorable vesting treatments. We see 88% participation, on average, if vesting is unchanged. If vesting is extended, that falls slightly to 85%, and if vesting is reset completely, participation drops to 79%. Of course, these simplistic averages don’t account for other program terms that may drive participation but still represent an interesting pattern.

#7. When should we lock our exchange ratios?

The exchange ratios—that is, the number of old options that must be surrendered per new award received—are a key element of any exchange program. For value-for-value programs, the exchange ratios are set based on the accounting fair value of the old vs. new awards. This raises the question of whether that fair value should be estimated (and ratio locked down) before or after the tender offer.

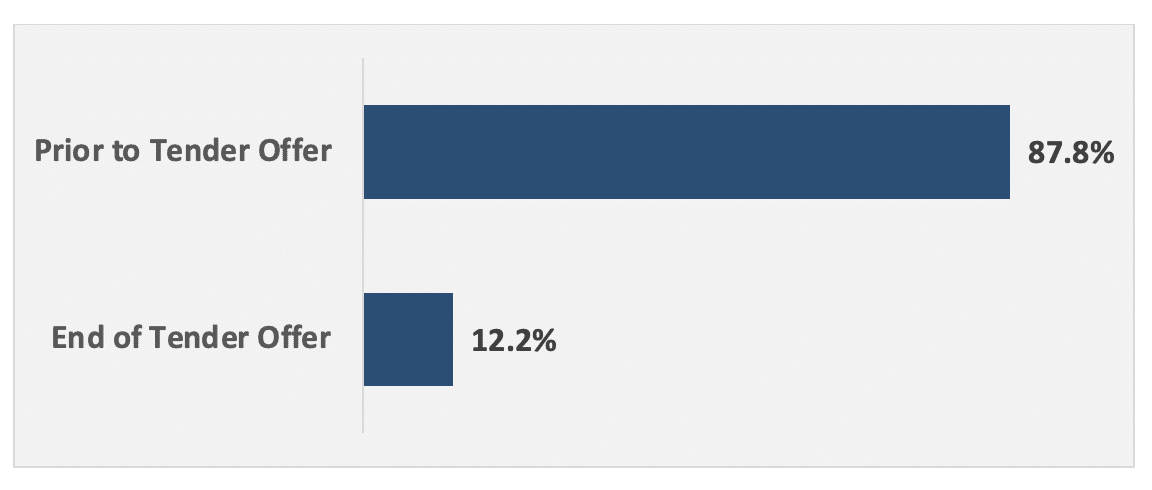

Since option exchanges require a 20-business-day tender offer period, there’s potential for market fluctuations that can affect the economics and the accounting cost of the exchange. Fixing the ratios pre-tender offer can provide clarity to employees at the price of uncertain cost outcomes. Waiting until after the tender offer period can provide certainty around cost, but may be unclear or confusing to employees. A large majority of companies prioritize the former and lock in their exchange ratios prior to the tender offer, though there are circumstances where the latter can be preferable.

Major Considerations

Cost Sensitivity. If the accounting cost of the exchange is sensitive and a truly cost-neutral (or zero-cost) exchange is critical, setting the exchange ratios after the tender offer period has ended can guarantee that outcome. Care should be taken to help employees understand how exchange ratios will be calculated since they’ll be asked to make decisions without ratios being explicitly set. Most companies will provide estimated ratios before the exchange, then caution that the ratios will ultimately be finalized after the tender offer period.

For most companies, though, some exposure to accounting cost based on market movements is palatable and expected even if the exchange is targeted to be value-neutral. In these cases, setting ratios before the tender offer period provides clarity and certainty so employees can make a fully informed decision. Interestingly, our data shows no significant difference in participation for companies that lock in the exchange ratios before versus after the tender offer period, though this may be due to other differences that exist between companies structuring their program each way.

Company Volatility. Highly volatile company stock may have a higher probability of substantial movements over the 20-day tender offer period, which may support the decision to wait until after the tender offer period to finalize ratios. Lower-volatility companies may be more confident that share price will be reasonably stable over that time period.

Wrap-Up

A carefully designed option exchange program can go a long way toward retaining employees and preserving the rewards strategy while still protecting shareholder interests. Firm-specific factors like company and shareholder profile, employee population, stock price history, and public visibility can substantially swing the pendulum on how to structure an exchange. Nonetheless, we find that market statistics such as these are helpful in guiding these company-specific conversations.

In addition to the sensitivity surrounding the design of the exchange, similar care and thoughtfulness should go into determining if an exchange should be offered at all. Option exchanges are highly visible because only a small number occur each year. Proxy advisory groups have strict guidelines that inform how they think about option exchanges in the context of recommendations for the program and subsequent say-on-pay and compensation committee election votes, and institutional shareholders’ voting policies are largely similar. In some cases, other equity strategies such as special grants or actions targeting key populations may be more palatable than an exchange.

Overall, option exchanges can be an extremely useful way to mitigate the enormous retention and incentive risks associated with prolonged stock price decline and deeply underwater employee stock options. To capture that benefit, these programs need to strike a tricky balance between the various interests of all stakeholders—the company, employees, and shareholders.

We hope the data and discussion above are helpful to your internal conversations. If we can be of any assistance or if you would like to discuss your particular circumstances, please contact us.