A Primer on the SEC’s New C&DIs for Pay vs. Performance

On Friday, February 10, the SEC issued its long-awaited Compliance & Disclosure Interpretations (C&DIs) for the rapidly approaching pay vs. performance (PvP) proxy disclosure pursuant to Item 402(v) of Regulation S-K (“Reg S-K”).

These C&DIs were released after three companies filed their first PvP disclosures, and after hundreds (maybe low-thousands) of companies showed near-final results to their compensation committees. That left us concerned about the possibility of disruption. Fortunately, the C&DIs were generally clarifying and did not trigger much disruption to in-flight preparation processes.

In this article, we’ll summarize each interpretation provided by the C&DIs, then share our reactions—with special attention to the topics where there are contrasting viewpoints on what the SEC is asking or instructing. But before going there, let’s look at two hotly debated topics that the C&DIs don’t address.

Topics Not Addressed by the C&DIs

It’s possible the SEC omitted the following topics because they understood major variation exists in practice and didn’t want to instigate costly course corrections this close to filing dates. That would suggest there may be forthcoming guidance later in the year.

Retirement Eligibility

The first is the treatment of retirement-eligibility awards. Recall that for equity awards, the last measurement date for calculating compensation actually paid is the vest date. The technical question is how to define the vesting date for purposes of this calculation.

One perspective is to assume that vesting occurs when the substantial risk of forfeiture lapses. For retirement-eligible (RE) awards, this would mean that the last measurement date is the RE date. Another approach, which we’re leaning toward slightly, is to use the legal vesting date as the last measurement date (unless an RE executive retires and vesting is truly accelerated). This view aligns to prior interpretive guidance that the SEC has provided regarding the vesting definition for retirement-eligible awards in the proxy’s Option Exercises and Stock Vested table.

Most practitioners have opinions of varying levels of intensity about the correct technical answer. But there’s little agreement, and this will be an extremely important area for the SEC to weigh in on.

Employee Stock Option Valuation

The second topic concerns the valuation of employee stock options. We devote an entire article to this topic, in which we share our principles-based view of the tradeoffs between simple and more complex methodologies. Although we’ve spent considerable time thinking through the various fact patterns and how to align them to reasonable valuation methodologies under GAAP, this is an area where competent professionals can certainly disagree and arrive at different conclusions.

One reason the C&DIs skip employee stock option valuation may be that the SEC wants to avoid being prescriptive, focusing instead on the language in the original rule pointing to a reasonable method in use under GAAP. Another possibility is that commentary will arrive later in the year, after the SEC reviews the first round of disclosures.

Topic-By-Topic Review of the C&DIs and Our Perspectives

Now let’s look at what the C&DIs do address. We’ll summarize each C&DI question and the SEC’s answer, then follow up with our own reaction.

Question 128D.01

Question Summary: Does the Item 402(v) PvP disclosure need to be included in the 10-K?

Answer Summary: No, because Item 402(v) may be incorporated by reference into the 10-K.

Our reaction: surprised.

We’re surprised this was a question. Executive compensation information required in the 10-K generally may be incorporated by reference, provided the registrant specifically incorporates it. The SEC discusses this process in Section G of its General Instructions to Form 10-K.

Question 128D.02

Question Summary: Do old awards issued to new named executive officers (NEOs) enter into the calculations? For example, if Jane Doe becomes an NEO in fiscal year 2022, would the awards she was granted in fiscal year 2020 be part of her compensation actually paid (CAP) calculation?

Answer Summary: Yes, because the premise of the CAP calculation is to track changes in award value. So while her CAP in fiscal year 2022 does reflect decisions the compensation committee before she became an NEO, the numerical value itself is driven by changes in performance in the current year in which she is an NEO.

Our reaction: not surprised.

Any other interpretation would yield a biased picture of compensation.

Question 128D.03

Question Summary: Do the detailed equity award adjustments underpinning CAP need to be footnoted for each fiscal year or only the most recent year?

Answer Summary: For the first year of disclosure, each year must be separately footnoted. Thereafter, only the most recent year must be footnoted unless excluding prior years is misleading.

Our reaction: not surprised.

We’re not surprised the SEC isn’t giving any shortcuts here, since the guiding framework seems to be giving proxy users every possible angle to pressure-test the results. In future years, disclosure of only the current year is required (unless omitting the prior years is misleading), since anything more would be duplicative. One reason omission could be misleading is if an error was identified such that the current year’s disclosure wouldn’t foot to the content in prior years.

Question 128D.04

Question Summary: Do the granular pension and equity award adjustment calculations need to be disclosed, or is it permissible to disclose only the aggregate adjustment for pensions and equity awards?

Answer Summary: The granular adjustments must be provided.

Our reaction: not surprised.

Our initial reading of the rule last August led us to conclude that aggregate figures would suffice. But since then, the SEC has signaled in unofficial communications that the granular breakout would be needed. As such, this answer isn’t a surprise. There are six equity award adjustments underlying the aggregate equity award adjustment that drives the crux of the CAP calculation. For EM clients, you’ve probably heard us refer to these as the six swim lanes of CAP:

- Full value of awards granted in the most recent fiscal year and that are outstanding at fiscal year end

- Full value of awards granted in the most recent fiscal year and that vest in the same fiscal year

- Fair value change of awards granted in any prior fiscal year that are outstanding and unvested as of the current fiscal year-end date

- Fair value change of awards granted in any prior fiscal year that are outstanding in the most recent fiscal year and that vest in the most recent fiscal year

- Reversal of the prior fiscal year end fair value for awards that forfeit in the most recent fiscal year

- Dividends or other earnings paid on awards in the most recent fiscal year that are not counted in the fair value

These six calculation swim lanes are standard to any robust process (and to our work product). The challenge is helping your executive team and compensation committee wrap their heads around so many moving parts and granular details. Obviously, compensation committees don’t review detailed reports. But in the course of trying to understand a particular result, the granularity behind the calculation becomes apparent.

This relates to a second challenge companies face: how to review and get comfortable with the calculations. We provide granular reports, reperformance models, and detailed walk-throughs to bring transparency to a complex process. For those using other vendors or doing this work internally, we suggest ensuring the calculations are done at the most detailed level and that you sample each calculation swim lane to make sure it’s doing what you expect it to do.

Question 128D.05

Question Summary: Is any peer group that is disclosed in the CD&A and used to help inform executive pay permissible as the basis for the PvP peer TSR calculation?

Answer Summary: Yes, as long as the peer group is disclosed in the CD&A and used to help set executive pay.

Our reaction: mildly surprised.

This is mildly surprising but not shocking. The original PvP rule referred to the peer list disclosed under Item 402(b) of Reg S-K, which discusses the CD&A in general. The question surfaced as to whether any peer group referenced in the CD&A is permitted—or, more narrowly, only a peer group that is explicitly flagged as being used for benchmarking purposes under Item 402(b)(2)(xiv). A conservative interpretation of the rule is that only the benchmarking group, if present, is allowable. A broader interpretation would view any peer group disclosed in the CD&A as fair game. The C&DI here favors the broader interpretation.

This still doesn’t answer one burning question: Can a company use the peer group used in its relative total shareholder return (TSR) program for its peer TSR calculation? Ostensibly, yes, because that peer group informs executive pay (it’s literally the group whose performance will dictate a payout outcome). However, we’re not sure the SEC had that much breadth in mind when drafting this CD&A comment. For example, what if the relative TSR (rTSR) peer group is a broad-market (instead of industry-focused) index? How would an rTSR peer list be viewed in light of Question 128D.07 of the C&DIs (discussed below)?

This debate may not be over yet. Hold tight before selecting your relative TSR peer group for this purpose.

Question 128D.06

Question Summary: What starting date should be used in the TSR calculations for registrants that went public during the time period covered by the PvP table?

Answer Summary: The go-public date, consistent with the calculation under Item 201(e) of Reg S-K.

Our reaction: not surprised.

The calculation of TSR beginning on the date the company goes public is logical and aligns with most companies’ prior interpretations. Note, however, that the questions of TSR measurement period and compensation measurement period for CAP are separate considerations.

For example, one may argue that regardless of TSR measurement, the CAP should span the entire fiscal year that is straddled by the go-public event (and not simply the stub year after the go-public date). Otherwise, compensation actually paid may arguably be understated for pre-transaction grants. This approach would requires retrieving prior 409A values and using these to perform the valuations that precede the go-public date.

In practice, we see variety in interpretation of when CAP measurement begins, depending on the type of go-public transaction (e.g., standalone IPO vs. spin from parent) and other facts and circumstances.

Question 128D.07

Question Summary: If using the CD&A peer group to calculate peer TSR, can the fiscal year 2022 peer group be used for all three years of the initial disclosure? Or must the peer groups used in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 be used for those respective years’ peer TSR calculations?

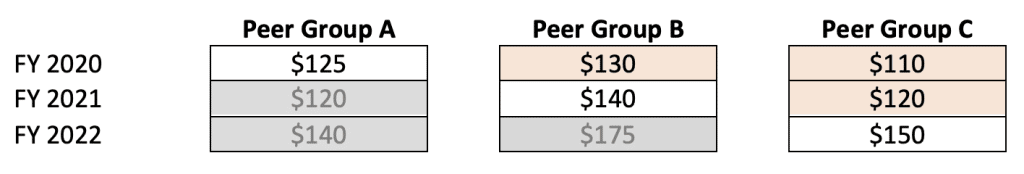

Answer Summary: The peer group applicable to each fiscal year should be used as the basis for the peer TSR calculation in each respective year. For example, if peer groups A, B, and C were in place in fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022 respectively, then peer group A is used for the fiscal year 2020 calculation, group B for the fiscal year 2021 calculation, and group C for the fiscal year 2022 calculation.

Our reaction: surprised.

We’d expect it would be satisfactory to use peer group C for each year in order to facilitate comparability. Of course, one or two companies might not have stock price returns going back to the beginning of the measurement period (e.g., fiscal year 2020). But that drawback seems to be outweighed by the benefit of comparability.

The following table provides an illustrative example. The red-shaded cells are the retrospective calculations for the new groups B and C. The gray-shaded cells are the peer group calculations that would have been used had the company not changed peer groups. Our preference for the sake of simplicity and comparability would have been to use only those results for Peer Group C, but instead the rule requires disclosure of the unshaded cells.

The final rule requires footnote disclosure of changes in the peer group, whereby you use the new peer group in the table and then disclose what the peer TSR calculation would have been under the old peer group. Whereas the context behind this rule is prospective peer group changes, we suggest for this first year of disclosure to footnote retrospective peer group changes as well. Strictly speaking, this would mean disclosing the gray-shaded results.

In addition, the C&DI seems to contradict the guidance included in the original rule release, which indicated that only the latest peer group should be used:

Consistent with the approach taken in Item 201(e) of Regulation S-K, as proposed, if a registrant changes the peer group used in its pay-versus-performance disclosure from the one used in the previous fiscal year, it will only be required to include tabular disclosure of peer group TSR for that new peer group (for all years in the table), but must explain, in a footnote, the reason for the change, and compare the registrant’s TSR to that of both the old and the new group.

It’s unclear whether the SEC intended to supersede that interpretation or if the inconsistency is resolvable.

Question 128D.08

Question Summary: Can alternative renditions of net income be used as long as they appear in the audited financial statements?

Answer Summary: No, bottom-line net income as defined in Regulation S-X is what’s required.

Our reaction: not surprised.

It’s been clear this has been the objective.

Question 128D.09

Question Summary: Can alternative renditions of net income or TSR be used as the company-selected measure (CSM)—that is, metrics that are derived from or similar to net income or TSR?

Answer Summary: Yes, the CSM can be any measure that is derived from or similar to net income or TSR.

Our reaction: not surprised.

The way we think about it is that if the calculation formula is different, even by a small degree, then it’s a different measure and qualifies. This is why you’ll see hundreds of different fields in databases like Bloomberg or S&P Capital IQ, since finance is filled with slight variations on a base of core metrics.

Recall that typically, outside of potential edge cases, we expect that CSM needs to be a metric used in the short-term or long-term plan adopted in the most recent fiscal year.

Question 128D.10

Question Summary: Can the CSM be the stock price, given the fair value of awards is substantially influenced by the stock price?

Answer Summary: No, not unless an incentive plan uses the stock price as a market condition. If the stock price (or a derivative of it) isn’t an incentive plan metric in the most recent fiscal year, but influences CAP by virtue of its overall effect on equity award values, this is not a sufficient basis for selecting stock price as a metric.

Our reaction: not surprised (but disappointed).

We’re unsurprised because the SEC appears very tethered to this idea that the CSM should be a financial metric in the most current incentive plan design. We’re disappointed because a less literal interpretation of the term “metric” would suggest that the very first metric decision the compensation committee makes is to structure its long-term incentive awards using equity or cash. Not every company issues equity-based awards, and the decision to use equity over cash has a monumental impact on pay delivery…based on the stock price. Nonetheless, we understand why the SEC clarified the decision that stock price isn’t a suitable CSM unless it formally appears as a metric in the incentive plan. And it’s helpful to receive confirmation that stock price is allowed as a CSM in limited circumstances.

Question 128D.11

Question Summary: Can the CSM be a multi-year performance metric that ends in the most recent fiscal year?

Answer Summary: No, the CSM must be a single-year metric.

Our reaction: surprised.

This is surprising both for practical and principled reasons. Practically, we saw nothing wrong with a multi-year metric being consistent with the table, as the TSR in the table is already a cumulative metric spanning the years of the table. In principle, we fear that a prohibition on multi-year metrics detracts from disclosure quality. For example, a company whose long-term incentive (LTI) is heavily based on three-year rTSR percentile ranking or three-year EPS growth cannot use that metric as their CSM, even though it genuinely is the most important metric. Further, a focus on single-year metrics in the table may overly encourage short-term thinking and decision-making.

Nonetheless, the rule is clear as written. For companies who were planning on using a three-year LTI metric, we generally suggest one of two approaches. The first approach is to keep the metric itself the same (e.g., adjusted EPS), and just display the one-year result in the table rather than the three-year version (i.e., adjusted EPS for the respective fiscal year instead of cumulative three-year adjusted EPS, which could be the LTI plan metric). This is likely cleanest in most cases. For cases where this does not work well, a second approach would be to switch to another metric that fits better as a single-year number, such as a metric from the annual incentive plan.

We have seen some industry professionals adopt an ultra-strict interpretation of this question in which they don’t perform a transformation of a three-year metric into its one-year equivalent. We don’t reach this conclusion based on the “user test”. What would a user of the financial statement prefer to receive: 1) nothing, or 2) a three-year metric transformed into its simple one-year equivalent? We think the answer would be number two, because any such transformation does not obfuscate the underlying metric and is more useful than doing nothing altogether.

Question 128D.12

Question Summary: Are the financial metrics governing a pool plan permissible as a CSM, even if the final individual allocations from the pool are subjective or not based on financial performance metrics?

Answer Summary: Yes, because CAP is influenced (albeit only partially) by those financial performance metrics.

Our reaction: not surprised.

Any financial performance metric that wholly or in part drives CAP is a viable CSM, as long as that metric is used in the most recent fiscal year’s incentive plan. This response also clarifies that if there’s any potential metric that qualifies as a CSM, then it should be used. There’ve been some views that the CSM is optional. Footnote 21 of the final PvP rule also clarifies that a CSM need not be disclosed if there simply isn’t a metric that meets the requirements. Otherwise, there’s no framework for simply choosing not to use a CSM.

Question 128D.13

Question Summary: If there are multiple principal executive officers (PEOs) in a fiscal year, can their CAP values be aggregated for purposes of the Item 402(v) relationship disclosures?

Answer Summary: Yes, as long as the result of doing so isn’t misleading.

Our reaction: not surprised.

This makes sense and will usually help the relationship disclosures be less misleading. We’ve discussed in other publications how finicky the PvP relationships can be in terms of surprising or counterintuitive movements. One of many causes is the presence of multiple PEOs. At the margin, we expect this will help some graphs make better intuitive sense. Other graphs will benefit from a clear separation of PEOs.

Question 228D.01

Question Summary: If a company changes its fiscal year during the time period covered by the PvP table, how should this be reflected in the table?

Answer Summary: Perform the calculations for the full fiscal years and the stub period created as a result of the fiscal year change. Then disclose all of these for the covered period. Maintain the stub period until it drops off the table due to it being more than five years prior to the current fiscal year. The example used by the SEC is a company that changes its fiscal year from June 30 to December 31. For its first year of disclosure, the top row in the table will be the stub period of July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022. The bottom row will be July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020.

Our reaction: not surprised.

This isn’t surprising and, as noted by the SEC, aligns with the approach used in the Summary Compensation Table (SCT). Wherever and whenever possible, our view is that the SEC is trying to drive uniformity with the SCT so that you can draw a line from the SCT to the PvP table.

Question 228D.02

Question Summary: If a company emerges from bankruptcy with a new class of stock that was issued under the bankruptcy plan, what should the starting point be for its TSR calculations in the PvP table?

Answer Summary: Both the company and peer TSR calculations may begin at the point of emergence. This is consistent with how the stock performance graph under Item 201(e) would also be constructed. A footnote disclosure should be provided that “explains the approach and its effect” on the PvP table.

Our reaction: not surprised.

This isn’t surprising since any alternative approach of trying to present the TSR calculations using a pre-bankruptcy or intra-bankruptcy starting point stock price would yield strange conclusions. We do, however, take note of the qualifier the SEC uses that a “new class of stock” must be issued under the bankruptcy plan. We encourage companies to speak with their securities attorneys to verify their specific emergence framework involved with the issuance of a new class of stock.

A Work in Progress

Most of the C&DIs clarify items for which there already was a general consensus. Unfortunately, though, a few items have conclusions that differ from the prevailing interpretation. Further, not all experts in the professional community agree with what some of the SEC’s statements actually mean in practice. As a result, some companies may receive different guidance from different advisors, hindering comparability until either the SEC or the private sector comes together to iron out those points.

As a participant in various industry roundtables and organizations, we will of course monitor trends and aim to influence them in light of how we and our clients interpret the rules. Meanwhile, if you have any questions about the topics we just covered—or would simply like to continue the conversation—please contact us or your EM representative. We look forward to hearing from you.