Alternative Cashless Exercise for Small-Cap Companies: New Financing Trend or Flash in the Pan?

Warrants have always been popular as sweeteners that companies use to close deals, and popular provisions evolve over time. Recently, we’ve seen an uptick in a somewhat unique variation, a warrant issued in an alternative cashless exercise.

As the SEC recently pointed out in comment letters, the mechanics of alternative cashless exercise can be very different from what the name implies, calling attention to a very common and benign feature. In fact, we’ve often seen companies get surprised by the amount of dilution and value alternative cashless warrants can have.[1] In this article, we’ll explain what the features are, how they work (including that dilution we just mentioned), and how the SEC has recently reacted to them.

Before we dive in, we invite you to visit our primer to get some background on warrants and why companies issue them. While the alternative cashless exercise features are different, the language typically mirrors traditional warrants—which are often issued concurrently—but includes an extra clause for the feature.

The Basics of Alternative Cashless Exercise

Let’s start with the differences between a standard cashless exercise in a warrant and an alternative cashless exercise feature. A standard warrant often allows the holder to exercise in two ways. One is to pay the exercise price in cash (cash exercise). The other way is to receive an amount of shares equivalent to the payout the holder would have gotten if they’d paid the exercise price and sold the shares immediately (cashless exercise). As a result, the settlement is for a reduced number of shares.

An alternative cashless exercise feature, however, enables the holder to receive the full number of shares without paying any exercise price. In fact, there’s often a multiplier resulting in more shares, as well as down-round adjustments that further increase the value. In other words, this feature guarantees the delivery of shares regardless of the exercise price, with no future benefit to the company.[2]

Consider this recent example. A company made an offering with the following clause in its agreement for its Series B warrants, covering both cashless and alternative cashless features:

The holder may elect to exercise the warrants through a cashless exercise, in which case the holder would receive upon such exercise the net number of shares of common stock determined according to the formula set forth below, as applicable.

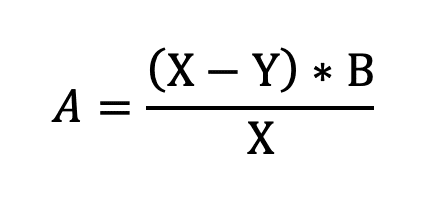

Where A = number of shares of common stock received upon cashless exercise

X = value of one share of common stock on the date of cashless exercise

Y = exercise price as defined under the terms of the warrant

B = number of shares of common stock received upon a regular cash exercise

Under the alternate cashless exercise option, the holder of the Series B Warrant, has the right to receive an aggregate number of shares equal to the product of (x) the aggregate number of shares of common stock that would be issuable upon a cash exercise of the Series B Warrant and (y) 3.0.

Note that no cash payment is required under the alternate scenario.

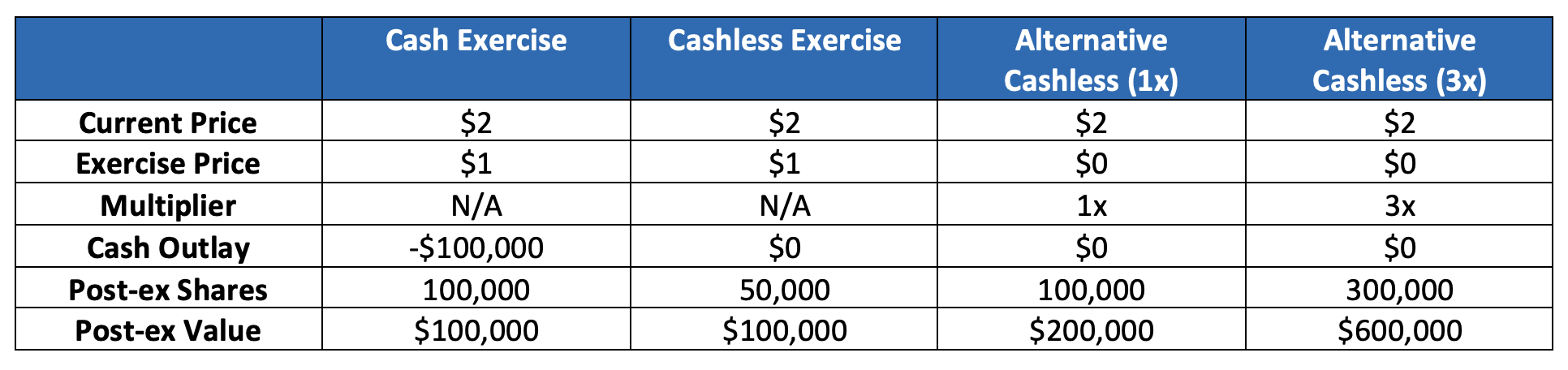

Now let’s walk through the features to understand the magnitude of payouts in these scenarios. Imagine you have a warrant for 100,000 shares with an exercise price of $1 per share and the share price on the exercise date was $2 per share (Figure 1).

- In a cash exercise, you’d pay 100,000 x $1 = $100,000 and receive $200,000 in shares for a net value of $100,000

- In a cashless exercise, you don’t pay an exercise price, but you get a reduced number of shares, 50,000, such that the net value is still equivalent to the cash exercise scenario, $100,000. This is also referred to as “net share settlement”

- In the case of the alternative cashless exercise, assuming a 1x multiplier, the holder will receive 100,000 shares at $200,000 value. Using the 3x multiplier from the above example, the holder receives 300,000 shares, and the value goes to $600,000

We can easily see from this example why investors have been seeking out alternative cashless exercise and why a holder of this warrant would always prefer this feature. The holder gets all of the shares (not just net of a strike price payment), and even in cases where the stock price falls below the exercise price, still holds a valuable security.

Reset Clauses

In addition to multiplying the number of shares, the exercise price of the warrants can be reset—often based on shareholder approval, a recent round of funding, or other pre-specified event. In this case, the warrant price may adjust to a pre-specified price or the lowest price the stock has traded at recently (typically subject to a floor). Once this happens, the number of warrants adjusts proportionally such that the original aggregate exercise price remains the same. As an example, if the exercise price is reset to $0.25 from $1, then the number of shares will increase by a factor of 4x, from 100,000 to 400,000. That keeps the aggregate exercise price at the same $100,000 as before the adjustment.

Such down-round provisions are common within warrants. In these cases, they often reflect a reduction to the lower exercise price (full ratchet) with an increase in shares. Because this lowers the stock price to a likely minimum and results in additional shares, it is generally the most liberal of such features.

Here’s an example of the language for another recent issuance:

On the 11th trading day after Stockholder Approval (the “Reset Date”), the Series A Common Warrants’ exercise price will be adjusted to equal the lowest of (i) the exercise price then in effect, (ii) the greater of (a) the lowest daily volume weighted average price of the shares of Common Stock during the period commencing on the first trading day after the Stockholder Approval Date and ending following the close of trading on the tenth trading day thereafter (the “Reset Period”), and (b) the Floor Price in effect as of the Reset Date, and (iii) the lowest volume weighted average price during the period commencing five (5) consecutive trading days immediately preceding the Reset Date, and the number of shares issuable upon exercise will be will be increased such that the aggregate exercise price of the warrants on the issuance date for the shares of Common Stock underlying the warrants then outstanding shall remain unchanged.

Naturally, once this happens, a larger number of shares are issued, and the share price can drop dramatically. But with alternative cashless exercise, the payout value can increase even when the stock prices declines (which is counterintuitive as most options pay less or even zero).

Payout and Valuation

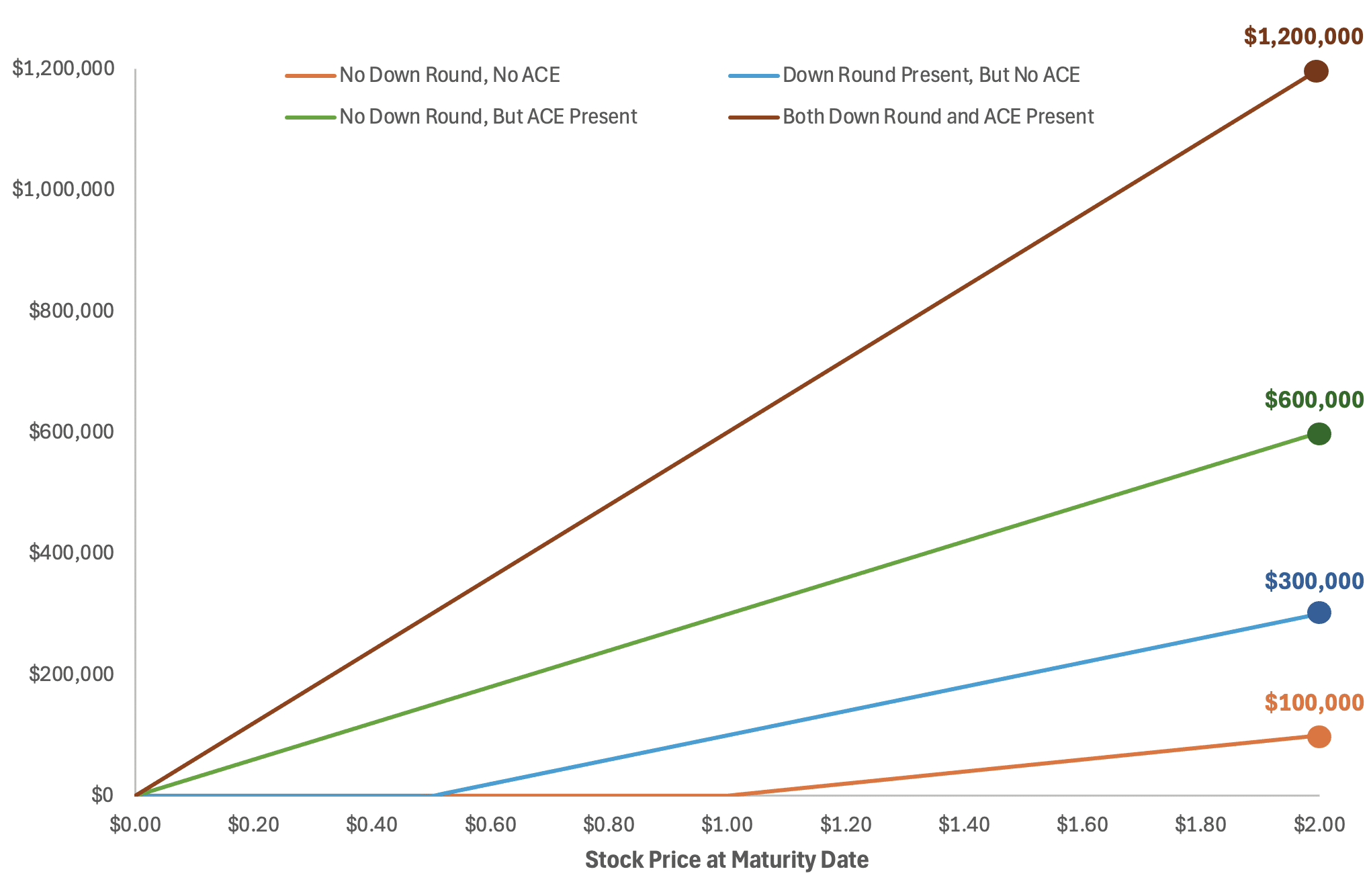

Figure 2 shows the payout values at different stock prices at maturity, visually demonstrating how these features create significant value to the holder.

- Base case: Holder can buy 100,000 shares at $1 exercise price (aggregate exercise price $100,000)

- Down round: If the stock falls below $1, the exercise price resets lower (e.g., $0.50), and the number of shares increases so that the aggregate exercise price stays $100,000

- Alternative cashless exercise: The holder can surrender the warrant and receive three times the normal shares that would be purchased in a cash exercise

- Maturity: Five years

Please refer to the Appendix for illustrative calculations for some sample closing prices.

As a summary, the presence of a down-round protection and an alternative cashless exercise provision could expose the company to high payments to the holder. Not only do the warrants get exercised at an effectively zero exercise price, the warrants also pay out to the holder if the stock price is below the exercise price, when traditional warrants would be expected to have no payout due to them being out of the money.

When valuing these securities, we have to incorporate the complexities of the payoff. Given their lack of exercise cost, these securities result in valuations of the underlying shares that are similar to penny warrants (the exercise price is $0.01, so the warrant value effectively acts like shares). Without a down round or projected financing, we typically use a fixed number of shares to calculate the fair value. However, in events where a future round of funding may cause an adjustment to the exercise price, a Monte Carlo simulation can be used.

Market Prevalence

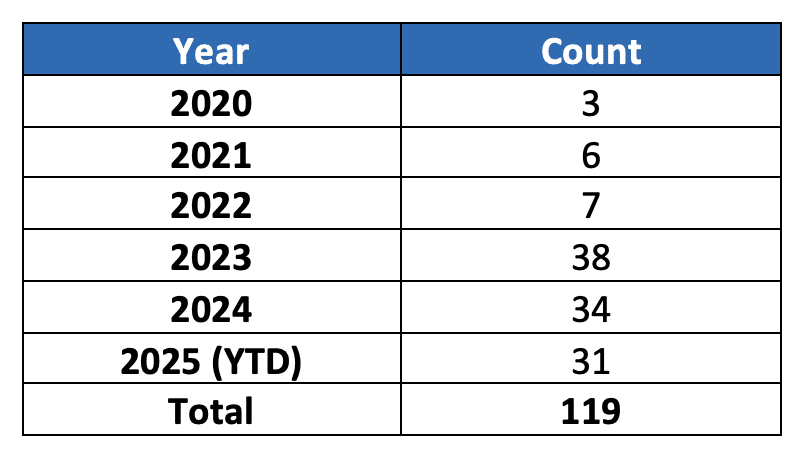

As public companies include these warrants in their filings, we have insight into market prevalence. A search of SEC filings from publicly traded companies over the past few years, through the end of June 2025, reveals that these terms became more prevalent in 2023 and continue to be popular (Figure 3).

SEC Commentary

Recently, we’ve seen a number of comment letters from the SEC in which public companies have been asked to revise their disclosures, changing the descriptive language from “alternative cashless exercise” to “zero exercise price.” To date, this has occurred in six SEC correspondences, five of them registration statements (S-1) and (F-1). The SEC implies this is intended to reduce investor confusion so that investors can fully incorporate the potential dilution from these instruments.

Here’s a recent example:

We note your disclosure indicates that you have an “alternative cashless exercise option.” Based on your disclosures…it appears that each Series B warrant could be exercised for 3 common stock shares on a cashless basis rather than for one share on a cash basis. Please revise your cover page disclosure to highlight that the…“alternative cashless exercise” provision would allow a Series B warrant holder to receive 3 shares of common stock without having to make any exercise payment, and provide a materially complete discussion of the impact of such exercise on existing shareholders. Explain that as a result you do not expect to receive any cash proceeds from the exercise of the Series B warrants because, if true, it is highly unlikely that a warrant holder would wish to pay an exercise price to receive one share when they could choose the alternative cashless exercise option and pay no money to receive 3 shares.

While these letters merely communicate the need for clarification, they may foreshadow further SEC scrutiny. Many market participants interpreted the SEC’s informal rulemaking activity on SPACs in April 2021 as an attempt to chill the SPAC market. Time will tell if the effect will be the same on this feature. Of course, we’ll keep an eye out for updates.

If you’ve issued warrants with these or other unique features—or are thinking about doing so—and need help modeling, understanding, or valuing them, please reach out to us.

Appendix: Calculations of Fair Values From Each Scenario

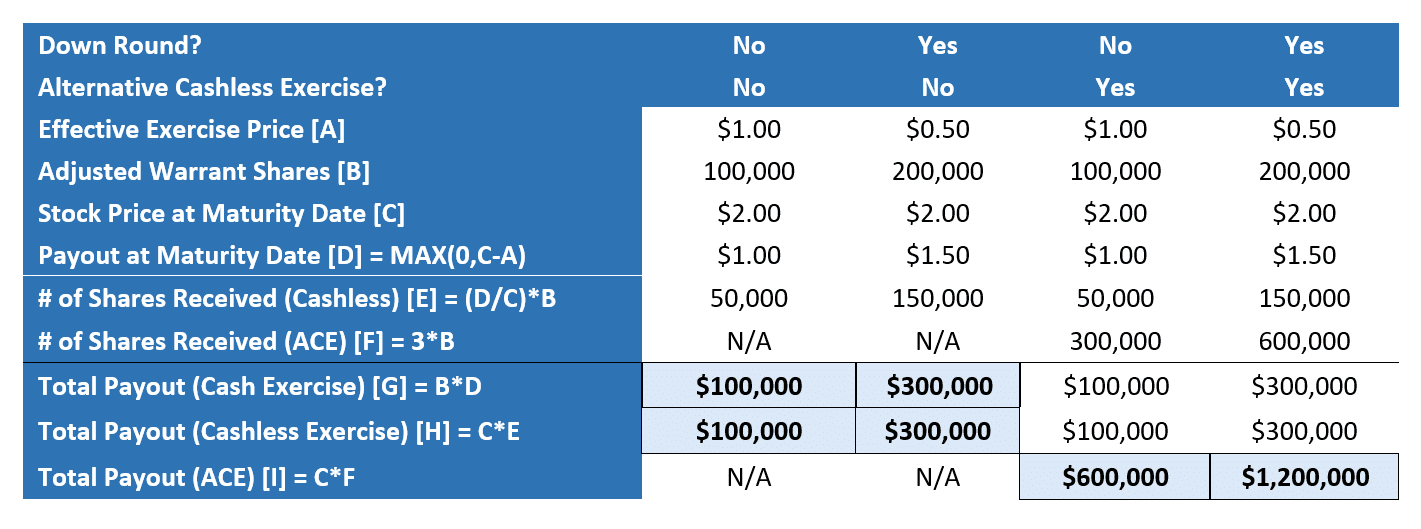

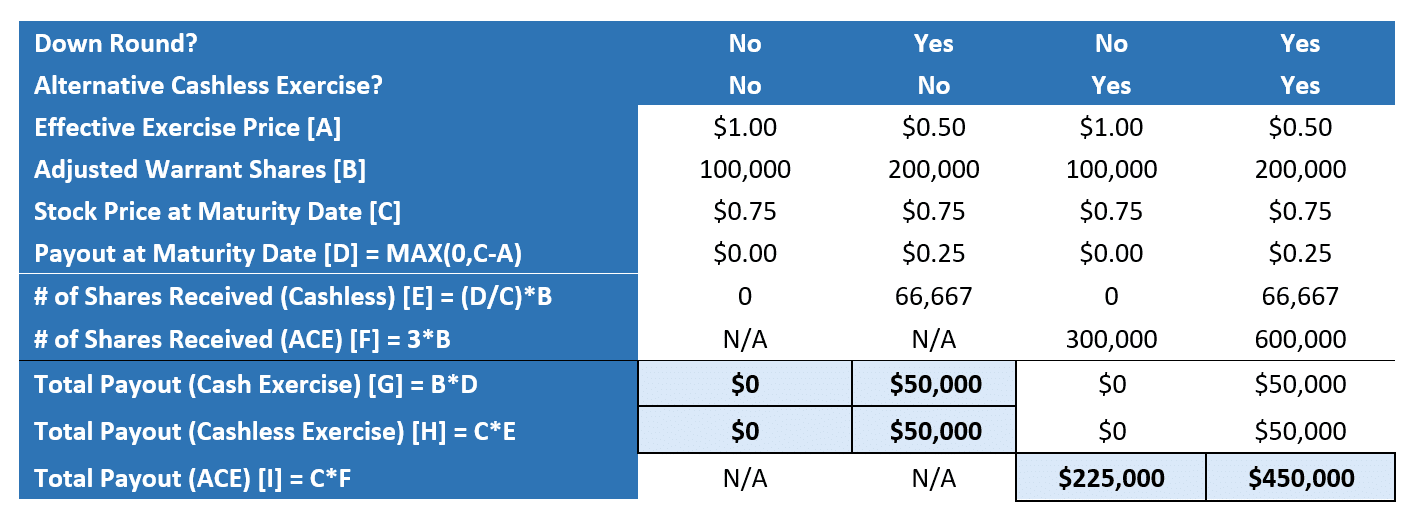

The tables below show the payout from the presence or absence of each of the features.

Scenario 1: High Ending Stock Price ($2.00)

Scenario 2: Low Ending Stock Price ($0.75)

No Down-Round Protection or Alternative Cashless Exercise Provision

In this case, there’s no adjustment to the exercise price and it stays at $1.00 no matter the stock price. The payout per share is just the higher of $0.00 or the stock price at maturity date minus exercise price. The aggregate payout is simply the payout per share multiplied by the warrant shares. There’s no payout if the stock price is below $1.00 per share.

Down-Round Protection Is Present but No Alternative Cashless Exercise Provision

In this case, the exercise price gets adjusted upon the occurrence of a down round (in this case, at $0.50 per share). As a result of the downward adjustment to the exercise price, the number of warrant shares also increases to 200,000 (such that the product of shares and exercise price stays at $100,000). Now, the payout per share at maturity date is the higher of $0.00 or the stock price at maturity date minus the adjusted exercise price. The aggregate payout is the payout per share multiplied by the adjusted warrant shares, which is 200,000. As a result, the value in this scenario is higher than that without a down-round protection because the holder gets an advantage of lowering the exercise price. In other words, the holder also receives value when the stock price goes down (provided a financing event occurs), which doesn’t happen under the traditional terms of a warrant.

No Down-Round Protection but Alternative Cashless Exercise Provision Is Present

In this case, assuming (for the sake of simplicity) a stockholder approval has occurred, the alternative cashless exercise feature (payout = 3x stock price at maturity date) is always going to have more value than the standard exercise (payout = max(0,stock price at maturity date – exercise price)). As a result, the aggregate payout at maturity date is simply 3x stock price at the maturity date multiplied by the number of warrant shares. The fair value for this scenario can be calculated simply as 3x stock price at issuance date times the number of warrant shares, with the idea that the fair value of a stock in the future is the stock price today.

Both Down-Round Protection and Alternative Cashless Exercise Provision Are Present

In this case, not only does the exercise price get adjusted upon the occurrence of a down round (in this case, at $0.50 per share), but the alternative cashless exercise feature also allows the holder to receive an increased number of shares from the down-round provision. Similar to the down-round case above, the number of warrant shares increases to 200,000 (such that the product of shares and exercise price stays at $100,000). Now, the payout from the alternative cashless exercise (again, assuming a stockholder approval has occurred) would be 3x stock price at maturity date x 200,000 shares, whereas the payout from a regular exercise would be 200,000 shares multiplied by the higher of $0.00 or stock price at maturity date minus the adjusted exercise price. Clearly, the payout from the alternative cashless exercise is always higher.

[1] Throughout this article, we refer to a warrant with an alternative cashless exercise feature as an alternative cashless warrant. Due to economics, we would expect all warrants with such a feature to exercise using the feature, as this always provides a higher value.

[2] Some readers may notice these look very similar to prepaid or penny warrants that have only a nominal exercise price. While the economics are similar, the down-round features are typically different and the deals that result in these features tend to have different characteristics.