More Best Practices in 10K Disclosures for Complex Equity Awards

ASC 718 recently went through some significant revisions with the adoption of ASU 2016-09. To our surprise, clarity went missing in the area of share-based payment disclosure guidance.

Disclosure quality is an ongoing theme with the SEC and PCAOB. At the most recent AICPA Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments, SEC chairman Jay Clayton explained how critical it was for disclosures to mirror business realities. In light of this, and the fact that the 10-K season is rapidly approaching, we’re sharing a few areas where we see risk in disclosures of equity compensation arrangements.

Disclosure Principles

Let’s start with the guidance in ASC 718 and the institutional principles behind that guidance. The relevant sections of ASC 718 are ASC 718-10-50-1 and ASC 718-10-50-2 (which includes amendments related to ASU 2016-09).

Importantly, ASC 718-10-50-2 begins by noting that the section represents the “minimum information” that’s needed to satisfy the disclosure principles it outlines. For this reason, we caution organizations to not take a check-the-box approach. Be especially cognizant of situations where the literal guidance is silent or incomplete.

The basic disclosure principle in ASC 718 is to explain “the nature and terms of such arrangements that existed during the period and the potential effects of those arrangements on shareholders.” Disclosure, according to Clayton, needs to explain how the business is actually operating: “If it results in quality, I’ll be really happy. And if it results in boilerplate, I’ll be really bummed out.”

There are a few areas in particular where share-based payment disclosures come up short.

Carve-Out Disclosures and Comparability

In their stock compensation footnotes, some companies offer a myriad of disclosure tables while others have only one or two. Why the inconsistency? And what does the guidance suggest is best practice?

Per ASC 718-10-50-2(g), issuers with multiple share-based payment arrangements should provide carve-out disclosures in the annual report according to award type “to the extent that the differences in the characteristics of the awards make separate disclosure important to an understanding of the entity’s use of share-based compensation.” It also says that liability awards and performance awards have characteristics that “could be important” enough to merit separate disclosure.

By default, this means separating options from full value awards, as these are fundamentally different instruments. But, of course, the existence of market, performance, and service conditions suggests even more detail may be appropriate.

The simplest solution is to provide separate tables for each distinct incentive design. That said, some companies may grant performance-based awards to only a few very senior individuals, leaving all other employees with time-based restricted stock. Broad grants of performance-based awards are very rare. Although performance awards are materially different, and generally warrant their own table, limited granting could justify lumping them in with regular time-based awards provided they’re still documented as footnotes under the respective tables.

But even that approach has holes since, from a principles perspective, users of financial statements may want to know that a performance award program is thinly utilized. That says something about the aim and intent of the compensation program. It also conveys something about potential dilution. Remember, performance or market awards have upside and downside, meaning they might ultimately be more or less dilutive than a time-based equivalent.

Of course, highly exotic designs such as performance options, cash awards, and non-employee awards should always be carved out.

Our conclusion: We prefer seeing separate tables for each distinct incentive design, because we think even small numbers can be valuable information. Still, it’s fair to lump small performance award plans into a broader plan that’s at least reasonably similar.

Performance Award Roll-Forwards

If the decision is to separate performance and market award designs, the next question is how to best present the roll-forward in the 10-K.

There are three general approaches:

- Base the 10-K roll-forward on the target number of units presented in the award agreement (“Target Units” approach)

- Base the roll-forward on the current expected payout (“Expected Units” approach)

- Base the roll-forward on the maximum expected payout (“Max Units” approach)

Consider the following case:

- Company ABC grants an award for 1,000 shares. The award can either pay out between 0% (0 shares) and 200% (2,000 shares), depending on the company’s return on equity (ROE) performance over a three-year performance period.

- One year into the performance period, Company ABC expects to pay out the award at 175%. As such, the company is expensing 1,750 shares to match this expectation.

Under the Target Units approach, 1,000 shares would be disclosed; under the Expected Units approach 1,750 shares would be disclosed; and under the Max Units approach 2,000 shares would be disclosed. Along those lines, it could even be informative to disclose the lower bound of possibilities (0 shares). There’s also the related decision of what to show in the formal disclosure versus what to explain in a sentence underneath.

Philosophically, we lean toward preferring the Expected Units in the roll-forward table. A standard way of structuring the table would be to show, on one line, the original shares granted (1,000). And then a second line could show the incremental 750 as the “Estimated Change in Performance Award Payout.” Then, at the bottom of the table, there should also be a disclosure noting that these awards can be paid out within some range of 0 to 200%.

Understandably, disclosing at the current expected payout brings about some challenges as the administration system may not capture the expected payout, only the target number of units granted. Once the payout is certified, the shares are updated to reflect the final payout. We use automated processes to bypass this issue for our clients. It’s also possible to disclose it as part of the one-sentence narrative beneath the roll-forward table.

Another challenge with disclosing Expected Units is that doing so may reveal too much information. Usually performance outcome expectations link cleanly back to guidance given to the street, but not always.

That segues into the alternative of only disclosing Target Shares, which in our example would be 1,000. Although reasonable enough, this approach doesn’t mirror the charge being recorded to the P&L. Neither will the disclosure be updated until the metric is certified three years from grant date.

From a principles perspective, consider again Clayton’s remarks about disclosures revealing what is actually happening in the business. A performance-based award should ebb and flow according to how the business is doing, so the disclosure should try to mirror that.

Users of financial statements will likely want to know how sensitive the incentives are to business performance. They’ll also wonder what sort of dilution to expect on these awards, and use the financial statement’s notes to construct forward-looking estimates. Whereas the Target Units approach will delay showing any changes in share counts until after the performance period has ended, the Expected Units approach shows changes sooner, thus allowing users to update their expectations. This is especially so when performance gains and losses are incremental and produce a smoothing effect on share count fluctuation.

Process and Technology Changes

Another disclosure area to monitor is the way in which internal process and technology changes are communicated. Companies frequently change their incentive plans and financial reporting systems. System changes usually introduce new methodologies, such as in how forfeiture rates are applied or mark-to-market accounting is performed. When that happens, companies have a couple of decisions to make. The first is whether they should reconcile the new output with the old. The second decision is whether to disclose such differences.

The relevant guidance is ASC 250 – Accounting Changes and Error Corrections, which offers three paths: a change in accounting principle, a change in accounting estimate, and a correction of an error.

Because system changes represent continuous refinements of older processes, they are typically treated as giving rise to a change in estimate. ASC 250 is careful to distinguish this kind of change from the kind intended to correct errors. In so doing, the guidance introduces a materiality framework. But ASC 250 also warns that materiality cannot be boiled down to a static formula.

Conceptually, stock compensation is full of estimates due to the large volumes of data and intertemporal calculations it requires. Except in extreme cases, standard practice is to treat new methodologies as changes in estimates. The reason is that they alter the way granular data rolls up into an overall estimate of expense.

Equally important, senior management needs to understand the drivers of variance during a system reconciliation. The way to tease out those drivers is to do the reconciliation at the individual grant level. Many reconciliations fail not because the two systems are producing unreasonably dissimilar results, but because management cannot accept what’s causing the minor difference that does exist.

Small but unexplainable reconciliation differences are problematic. There might be offsetting variances that seem immaterial, but in future years move in the same direction and thus trigger material variances. From an internal control over financial reporting (ICFR) perspective, it’s necessary to document that differences are explainable and can be linked to specific changes in estimation methods. Dashboards and drill-down tables help all parties cleanly explain the adjustment drivers.

In his talk on disclosure effectiveness, Clayton emphasized the important role that audit committees play in asking difficult questions. SEC chief accountant Wes Bricker added that awareness and training are important to both audit committee members and those preparing the financial statements.

Relating this to stock compensation, one inherent challenge is that equity awards introduce both considerable theoretical complexity and raw systems complexity. The danger that senior finance leaders face is they may get comfortable with the accounting policies, but could become highly removed from the way these policies are applied to granular data. This is especially concerning when dealing with spreadsheet-heavy processes. To catch problems before they compound, a strong and comprehensive system of internal control is needed. Stock compensation controls should focus on movements or changes in the data, special transactions (e.g., modifications and dividend protection features), complex award designs, and linkages between expense and tax reporting processes.

Mark-to-Market Considerations

Many companies use cash awards in their incentive programs. Cash awards do not burn shares, making them convenient for companies with share pool challenges.

Cash awards are classified as liabilities under ASC 718, and therefore revalued each quarter until settlement. Options and TSR-based awards require a valuation technique that’s robust to the facts and circumstances. For options, that would be a lattice model since Black-Scholes begins to break down after the grant date (the expected life assumption should be updated in the context of the option’s moneyness). For TSR-based awards, the valuation technique is a Monte Carlo simulation, making sure to incorporate realized performance through the reporting date.

But disclosures of mark-to-market situations can be confusing even when the accounting is right. Companies can manage this by explaining the terms of the instrument giving rise to liability classification (usually this will be a cash feature, but not always). In the disclosure, it should be clear whether the award is linked to share price fluctuations but pays out in cash, or altogether denominated in a fixed cash amount.

The disclosure should also reveal how the company is valuing the instrument. Users of financial statements will need to understand how the fair value estimation method is picking up changes in value. A separate table is generally called for to depict these valuation assumptions, since they’re likely to be different from those used on any plain-vanilla awards.

Whereas ASC 718-10-50-2 is relatively clear that liability awards merit separate disclosure, one peculiar question is whether to disclose the grant-date fair value or the mark-to-market fair value. A literal reading would suggest using the grant-date fair value. A principles view would suggest using the mark-to-market fair value, as it will yield better alignment to the expense being recognized and carrying value of the liability. We’ve seen both practices adopted.

Modifications and Corporate Transactions

Modifications, which include corporate transactions, require special disclosure because they involve changes to the portfolio of awards in place. This gives rise to potentially new incentive, dilution, and valuation outcomes—all of which are important for users of financial statements to understand.

The disclosure requirements for modifications are specifically called out in ASC 718-50-10-2(h)(2), which states that:

A description of significant modifications, including:

(i) The terms of the modification

(ii) The number of employees affected

(iii) The total incremental cost resulting from the modificationneed to be disclosed for each year that the income statement is present.

Broad-based modifications were prevalent during the recession of 2008. Today, modifications are usually one-off deals for terminating executives. (Awards assumed in a business combination or converted in a spinout are, of course, an exception.) Apart from very immaterial cases that involve neither executives nor material award changes, best practice dictates disclosing the items in ASC 718-50-10-2(h)(2) in the footnotes.

A very active flavor of modification occurs when companies assume the awards of another company that they acquire, or when they convert equity in a spinout transaction. Both types of corporate transactions affect equity compensation and, as such, need to be reflected accurately in the disclosure tables.

Let’s start with business combinations.

Acquisitions are quite prevalent in today’s business environment, and frequently acquirers choose to assume the awards of the acquiree instead of simply cashing them out. Materiality will generally dictate whether an altogether separate disclosure is warranted. Either way, the number of shares assumed should be included in the roll-forward table. A separate line (“Shares assumed through acquisition”) can help avoid confusion and keep the table cleaner. If the shares are not material, they can be included in the “Shares granted” line with a brief note explaining what was done.

For material acquisitions, the disclosure should include a discussion of any changes made to the terms of the awards assumed and whether the transaction gave rise to incremental cost. It’s also useful to include some discussion of the fair value accounting which, under ASC 805, requires bifurcation between consideration transferred and future expense to be recognized in the post-combination financial statements.

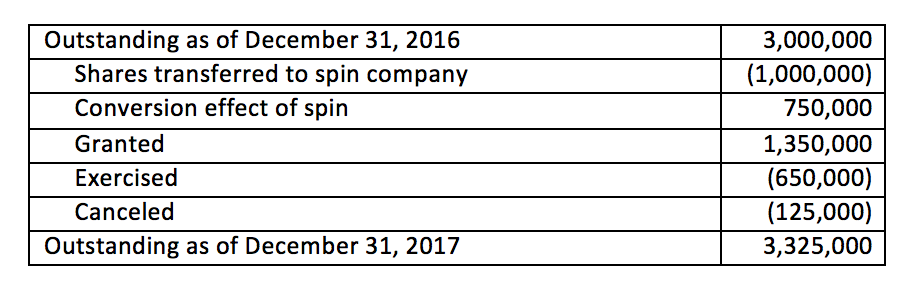

Spinouts are nuanced transactions that are not closely covered in ASC 718. They’re actually a type of modification. A few things occur in a standard spinout transaction:

- Shares are removed from the spinnor’s equity balance and transferred to the spinnee

- Those shares transferred are converted according to some formula, whereby the intent is usually to preserve the intrinsic value to the recipients

Of course, this can be done in many different ways. One notable policy decision is whether to give employees equity in both companies (the “Shareholder” approach) or only the post-spin entity employing them (the “Employee” approach).

There are no hard-and-fast rules about disclosing a spin transaction in the financial statements. But we can start by appealing to the spirit of the guidance: What information is relevant? Often, investors would at least like to know the following:

- The number of shares that were transferred from the spinnor to the spinnee

- The conversion factor used to formulate how many shares would be moved

- The incremental cost, if any, arising from the conversion

- The method used to convert awards (Shareholder or Employment approach)

For complex plans, this may require separate commentary by award type.

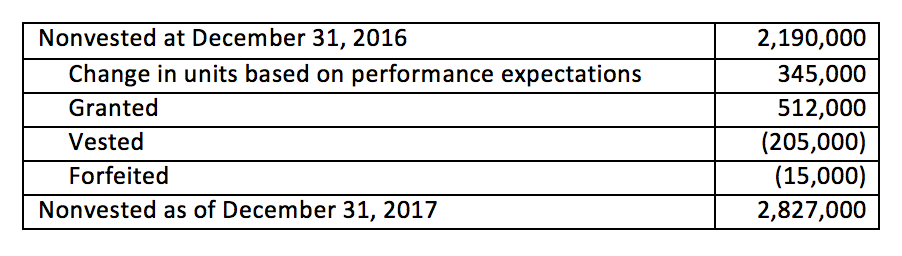

The first two items should appear in the roll-forward table as illustrated below. The last two items should be disclosed at the beginning of the Share Based Compensation Footnote section.

Putting it All Together

In disclosing their equity compensation arrangements, companies must somehow balance pithiness with enough context for readers to understand specifically what is happening. The way to do this probably isn’t by emulating a few peer firms. We’ve reviewed enough disclosures to realize there’s just too much diversity in how companies disclose the same kinds of transactions.

Instead, consider the message from the current SEC chief, and use whatever language clearly explains the underlying reality of how equity arrangements are being handled. This may result in some extra disclosure. But sometimes, all it takes is another two or three well-chosen sentences. That’s a small enough tradeoff for clarity.

We welcome the chance to discuss our experiences with disclosures. Please contact us anytime.