Companies with Visionary Human Capital Strategies Get a Boost from Regulation S-K Modernization

This fall, the SEC adopted Release No. 33-10825, Modernization of Regulation S-K Items 101, 103, and 105, which is effective as of November 9, 2020. Already, companies such as Starbucks, Visa, and Dolby have adopted the new standard in their 10-K filings published shortly after the effective date.

For a long time, many argued that the general business description (Item 101) and risk factors disclosure (Item 105) in the 10-K had become antiquated and populated with uninformative, boilerplate language. Our interest here is in the revision to Item 101(c), which focuses on how an organization manages its human capital. From both a labor economics and societal perspective, the role of human capital in our modern economy is nothing like it was 30 years ago when the rules were last revised.

The SEC’s recent revisions are for the most part principles based. Although many claim this waters down their effectiveness, we view the changes as a monumental first step and worry that anything more would have been too much, too soon. After all, for the first time ever, companies are now required to discuss on the face of the 10-K their human capital management strategy—including the metrics they use for measurement and monitoring. Between broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) tailwinds and the onset of a new political administration, we wouldn’t be surprised to see more disclosure requirements in a few years.

Background on the rules

The final rules amend the following four items in Regulation S-K (Reg S-K):

- Item 101(a), which is the general description of the business

- Item 101(c), where the human capital management topics are covered

- Item 103, which pertains to governmental environmental proceedings

- Item 105, which is a discussion of risk factors

The SEC revised Item 101(c) to include disclosure of the company’s “human capital resources to the extent such disclosures would be material to an understanding of the organization’s business.” Currently, Item 101(c) lists 12 topic areas, many of which were introduced in a 1973 release and may not be particularly relevant today (e.g., dollar amount of backlog orders). At the same time, the only requirement to discuss human capital is a disclosure of the number of persons employed, which is hardly insightful in light of the existential role that human capital plays in modern organizations.

That particular disclosure, Item 101(c)(1)(xiii), is where the revision is most consequential. The final rule now requires

A description of the registrant’s human capital resources, including the number of persons employed by the registrant, and any human capital measures or objectives that the registrant focuses on in managing the business (such as, depending on the nature of the registrant’s business and workforce, measures or objectives that address the development, attraction and retention of personnel).

Not much, right? There was considerable debate as to whether the final rule should be prescriptive or principles based. The SEC’s decision was 3-2 because two of the commissioners felt this brevity and lack of specificity would create a race to the bottom. We disagree. To the contrary, we expect either a race to the median—and maybe, gradually over time, a ratchet effect if companies try to one-up each other in sending positive signals to investors. Any upward ratchet effect will be counterbalanced by the higher risk level of a 10-K disclosure relative to the fluffier corporate social responsibility report.

The north star guiding this revision is clear: Investors are asking for more information on human capital management and the 10-K will need to respond to analysts’ and investors’ top areas of inquiry. When the 10-K is not responsive, buying and selling takes place, not to mention proxy voting resolutions that create pressure for the board of directors. Certain industries will invariably lead and others will lag, since human capital isn’t equally important across all industry sectors. But by and large, we expect the 10-K of the future to devote more energy toward metrics and analysis that are not purely GAAP financial in their nature.

What will be disclosed?

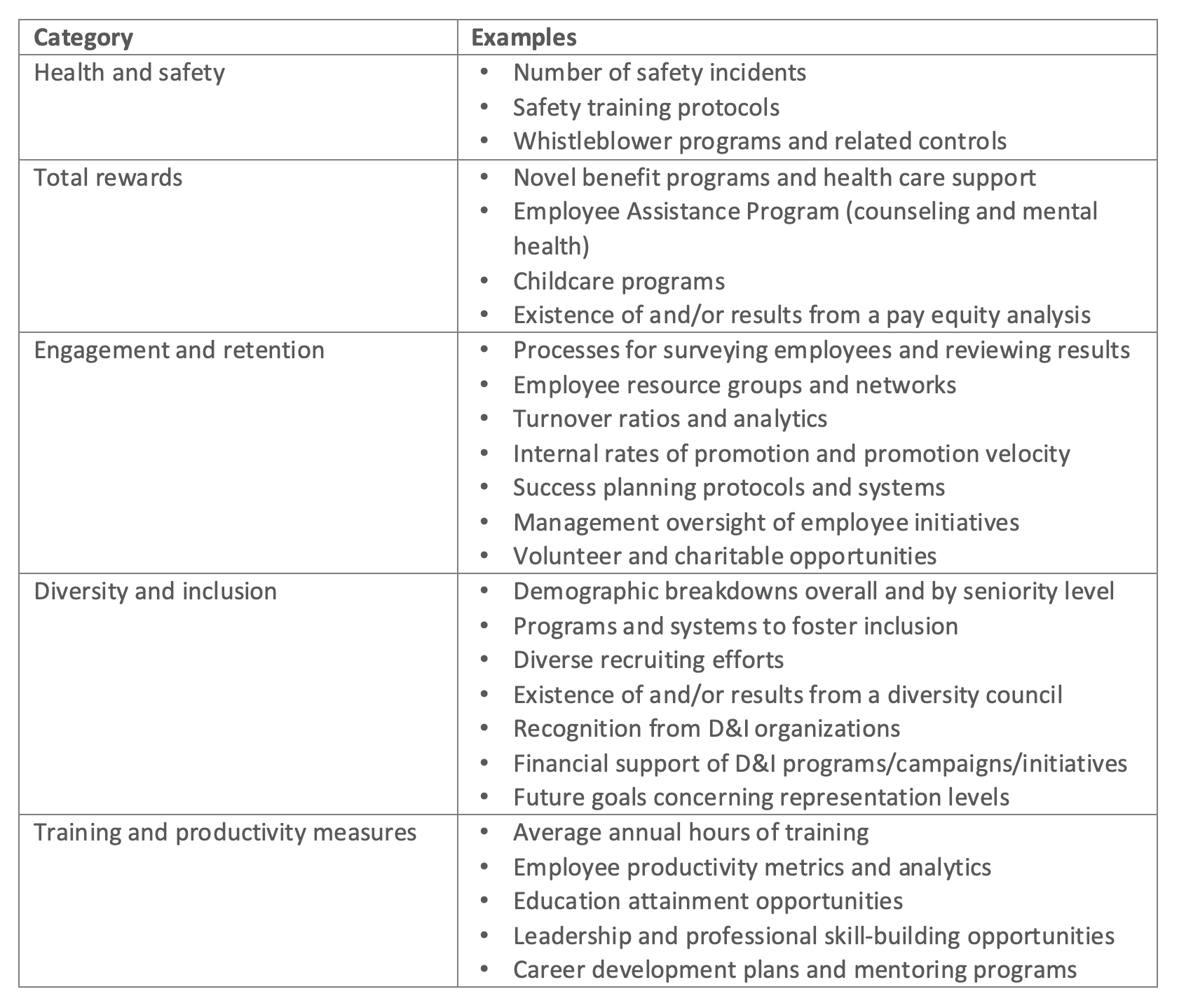

Previously published disclosures serve as a guide. In our next article, “Human Capital Strategy Disclosures Under Regulation S-K: A Tale of Three Companies,” we’ll review three actual disclosures in detail. Generalizing to the market as a whole, however, we expect to see disclosure across the following categories:

A couple of salient questions exist:

- Decision to disclose specific future targets. There’s a major difference between disclosing current levels on a metric like employee diversity and publicly committing to a goal in the future. While public commitments are often found in the CSR report, making them on the face of the 10-K has much more gravitas. One of the examples we’ll cover, Visa, made such a commitment in its own 10-K disclosure.

- Coverage of global or US-only metrics. Most companies share global metrics where available, but otherwise focus on their US metrics where the data quality is better. Additionally, diversity metrics don’t translate outside the US as well given limited tracking. For example, putting a magnifying glass over China would require obtaining data on the subgroups within China whereas an all-company focus currently involves categorizing all employees in China as Asian. This is likely to be an area for future tracking and enhanced disclosure, but may not be part of a firm’s earlier disclosures.

10-K, the audit, and controls

While the 10-K of the future may look much different from the 10-K of yesterday, we need to acknowledge that the 10-K at its core is a financial document. Auditors thoroughly test reported amounts to ensure they’re developed in accordance with GAAP and reflect the underlying economic reality of the business and its transactions. A second component of the financial statement audit is the audit of internal control over financial reporting (ICFR), an outcome of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

Currently, there isn’t a particularly robust way to audit non-financial numbers for which few to no auditable standards exist. A very simple example is pay equity: What does it mean to say your company has achieved 100% pay equity? Those of us who are experts in the field argue this means that an econometrician must build a multivariate regression model to test whether there are statistically significant pay differentials between otherwise like employees and after controlling for applicable variables. But not everyone defines pay equity that way and even experts can disagree over the most appropriate specification of a regression model.

Since the 10-K is a filed document with the SEC and is used as the basis for investment decisions, the disclosures in Item 101(c) should take on a higher evidentiary burden. This creates a challenge for accounting leaders faced with integrating these new disclosure requirements. As we’ll discuss in the third article of this series, “Human Capital Management: Deciding What to Disclose in the 10-K,” the starting point is to ensure adequate controls for these calculations. When we do this work, we develop automated processes with detailed tie out reports to support testing and review.

Equally important is to arrive at a clear internal understanding of what the metric does and does not measure to ensure the disclosure matches the underlying numerical framework. For this reason, we find that policy memos supporting all disclosed metrics (much like standard accounting memos) help ground internal stakeholders and identify disconnects between them.

As someone who practices in the intersection of accounting and compensation, I’m particularly intrigued by what these changes mean, what trends they’ll set in motion, and even whether the 10-K construction and auditing process is ready for them. In my next article, we’ll review a few salient examples from companies that have already adopted the new rule. After that, I’ll introduce a framework for deciding how to structure your own organization’s disclosure.