ESPP Accounting: Top 4 Pitfalls to Avoid with the IRS Contribution Cap

Employee stock purchase plans (ESPPs) are a fantastic tool in any total rewards program. They’re cost effective, offer employees a guaranteed return on investment, and help foster an ownership culture. All this has made ESPPs more popular than ever.

In recent years, increasing market volatility has put a spotlight on one of the more basic aspects of ESPPs: the mechanics surrounding the IRS contribution cap calculations. The contribution cap is nuanced even in the calmest of times, but can become quite complex when turbulence hits. Still, the contribution cap is critical to get right—a plan that’s not operated in accordance with Section 423 of the Internal Revenue Code can lose its tax qualification status.

In this article, we’ll address the top four pitfalls we see arising with internal and external scrutiny of IRS cap mechanics.

Getting the Basic IRS Cap Calculation Right

To set the stage, here’s how Section 423(b)(8) of the Internal Revenue Code defines the cap on ESPP contributions (which we’ll refer to as the IRS cap):

Under the terms of the plan, no employee may be granted an option which permits his rights to purchase stock under all such plans of his employer corporation and its parent and subsidiary corporations to accrue at a rate which exceeds $25,000 of fair market value of such stock (determined at the time such option is granted) for each calendar year in which such option is outstanding at any time.

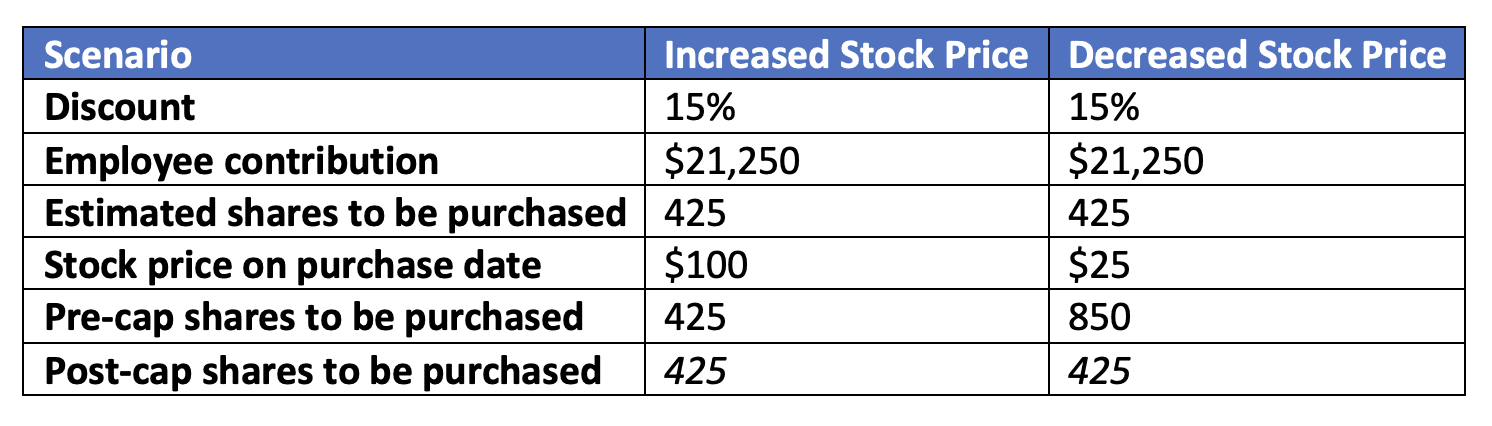

In other words, the rule states that no employee can purchase more than $25,000 worth of stock per year, as defined on the grant date. Assuming a 15% discount, this translates to $21,250 worth of contributions to purchase that stock.

However, since the value of the stock for IRS cap purposes is determined on grant, this is effectively a share cap. It sets a maximum number of shares that can be purchased, and this ceiling is fixed on the grant date. Thinking of the IRS cap as a share cap is important, as more complex plans can muddy the waters with a varying number of shares that can be purchased pre-cap. Consider the following example of a plan with an offering-date stock price of $50.

Despite the ability under the plan terms to purchase more shares because of the lower stock price, an employee at the IRS cap is limited to purchasing just 425 shares since the cap rule is based on the offering-date stock price.

Pitfall #1: Managing the Cap Rollover Across Years

One feature of the IRS rule is that it allows any unused cap space from the prior calendar year to be rolled over into a new calendar year when an offering straddles multiple calendar years. This would mean that in some circumstances, employees may be able to purchase more than $25,000 worth of shares in a single year. We usually see three scenarios where this happens:

- If you start a new offering in late 20X3 with a purchase in 20X4, where no prior offering existed or no purchases were made in 20X3, you get to roll over the full $25,000 of the 20X3 cap to 20X4

- If you had a purchase(s) in early 20X3 and then start a new offering in late 20X3 that will have a purchase in 20X4, then any cap space left over from 20X3 can be added to 20X4

- If you have a longer offering with multiple purchase periods, then unused portions of one year’s cap can be rolled forward into the next year’s cap, as long as the broader offering extends into that subsequent year

In cases like these, you’ll need to keep close track of each year’s IRS cap and how much the employee is utilizing in order to manage the ESPP effectively, maintain its tax qualification under Section 423, and get the accounting right.

Pitfall #2: Understanding the Cap Effect on Expense Amortization

The effect of the IRS cap on expense amortization is another oft-misunderstood area. This stems from the cap causing an uneven share distribution in many multi-period plans.

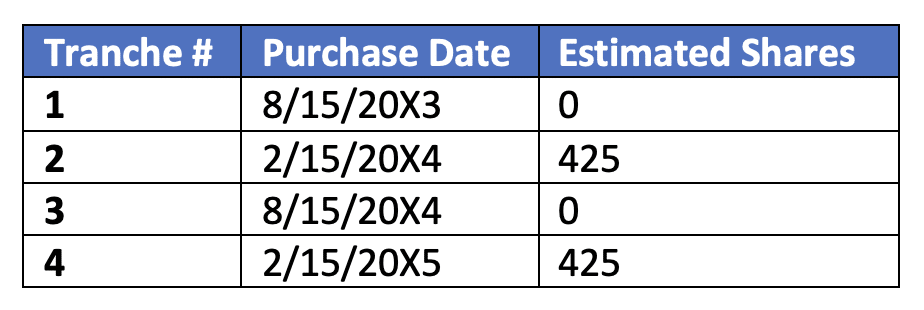

Consider a 24-month plan with four purchases (or tranches) that naturally span across multiple calendar years. In these cases, especially when a purchase has already occurred in the calendar year, the IRS cap can be fully utilized already, leaving the first purchase with zero shares. Here’s an example where a purchase on 2/15/20X3 from the prior offering had exhausted the cap for that year:

With both August purchases fully capped out and no shares estimated for purchase, it raises a common question: will we accrue no expense for the period between 8/15 and 2/15, then restart expense after 2/15?

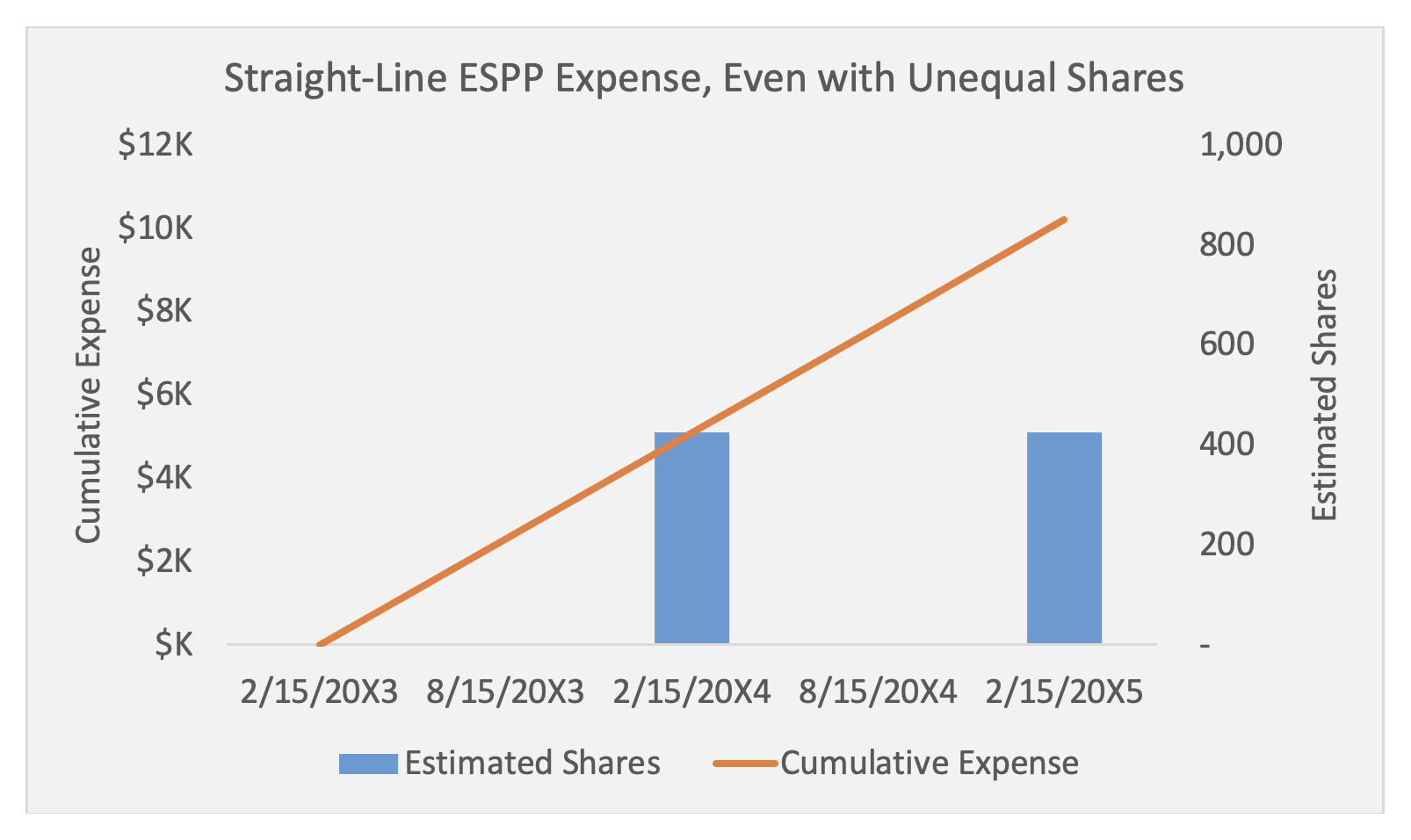

The short answer is no, expense does not stop and restart. Instead, straight-line principles should be applied in the same way they would for a traditional RSU grant with uneven vesting. Here, the goal would be to evenly distribute the expense across the entire life of the award. Consider the chart below:

Although the estimated shares are uneven, the expense remains a straight line over the life of the offering, with the straight line based on the total number of estimated shares versus spiking up and down for each purchase.

Pitfall #3: Applying the Cap to Contribution Modifications

Some plan designs allow employees to modify their contributions during offering periods. While this was historically uncommon, we have seen an uptick in these designs in recent years as companies leaned into their ESPP as a reward tool by maximizing flexibility. While there are a few pros and cons of allowing these adjustments (including modification accounting) that are outside the scope of this article, we find that the IRS cap creates a challenge for many companies with this feature. This challenge is surmountable, but often catches companies off guard the first time.

Recall that the IRS cap is, in substance, a share cap based on the offering-date stock price. This means that any contribution modifications are still subject to this same cap. In other words, if a particular tranche is already capped, then increasing contributions doesn’t translate into purchasing more shares.

However, another corner case involves tranches that are close to capped, but not there yet. We’ve seen many companies whose tracking systems (especially if they’re spreadsheet-based) treat the cap as binary. That is, the calculation sees that the tranche isn’t capped yet, and it (incorrectly) adds the full contribution modification. Systems need to be robust enough to only adjust estimated shares up to the original cap amount when contributions are increased.

To understand how this works, imagine a five-gallon bucket with four gallons of water in it. No matter how much extra water you have (the contribution modification), your bucket can only accommodate one more gallon. This analogy can be extended when you have multiple contribution modifications over the course of a longer offering.

Pitfall #4: Applying the Cap to Resets and Rollovers

Resets and rollovers have been the subject of increasing attention lately. They’re triggered in eligible multi-purchase offerings when a subsequent offering price is lower than the existing offering’s price. This will lead to incremental cost for both the additional shares that can be purchased and the incremental fair value per share. Rollovers also add more post-rollover tranches. In the context of the IRS cap, those different pieces of the puzzle are treated differently.

Continuing the water bucket analogy from before, if the bucket has some water in it already, then we can only fill up what’s left. This affects the incremental shares and the post-rollover tranches portions of the modification accounting by capping their impact, since they both represent actual shares to be purchased.

However, the incremental fair value piece is purely related to price movements—it doesn’t indicate shares to be issued. Therefore, it doesn’t affect the IRS cap calculation at all. But it does mean that the impact of the incremental fair value per share will be recognized in full, up to the individual’s number of purchasable shares.

Finally, rollovers in particular present one additional wrinkle. Because a rollover is substantively a new enrollment, an employee will lose any unused cap from prior years at the time of the rollover.

Naturally, keeping track of this can get quite complex, especially if there are multiple modifications stacking on top of one another from rollovers and contribution modifications. If you’re facing any of these situations, please feel free to contact us. We’d be happy to help you with tracking and with implementing solutions.

Closing Thoughts

ESPPs remain a wonderful way to deliver outsized value to employees at a very efficient cost. However, market volatility can put any accounting process to the test. This is especially true with more lucrative plans that have additional complexities built in, but even standard plans aren’t immune. Regardless, a well-thought-out, automated process is essential to ensuring accuracy and mitigating risk.

If you have any questions about ESPP accounting or design, whether you currently have one or are researching your options, please don’t hesitate to reach out.