Notice Periods for Retirement Eligibility

Earlier this year, we wrote about how to evaluate whether to include retirement eligibility (RE) provisions in a long-term incentive plan (LTIP). We noted that RE provisions aren’t for everyone. In fact, we’re working with just as many companies looking to adjust or disassemble their RE program as we are with companies looking to implement one.

Traditional RE programs can support both talent attraction and retention goals. But they also lead to an expense spike at grant, allow key talent to exit around the same time of the year during annual vesting events, and potentially shift benefits away from younger employees who plan to remain with the company. These issues give many organizations pause.

Enter notice periods. A notice period requires retirement-eligible employees to formally provide notice of their intended retirement in order to access favorable vesting provisions. If the notice period is substantive, meaning the company adheres to the policy and doesn’t have any pattern of waiving it, then this can provide vital time to plan for key talent departures and mitigate expense spikes on the grant date.

Here we’ll look more closely at the role of notice periods and how they can solve problems inherent to traditional RE provisions. We’ll begin by reintroducing RE frameworks in general. Then we’ll go into the nuances of a notice period, from how they work (including pros and cons) to the downstream reporting implications.

Retirement Eligibility Provisions

As a refresher, RE criteria is usually based on one of the following:

- A singular condition (one age or tenure threshold)

- An “or” condition (reaching either an age milestone such as turning 62 or a tenure milestone such as 20 years of continuous service)

- An “and” condition (reaching a combination of age and tenure milestones, such as age 55 and 10 years of continuous service)

- Additive condition (for example, the sum of age and tenure must be at least 65)

Once a company has decided on the RE criteria, there are two more decision points. The first is what portion of the unvested award will be retained upon retirement. The second is whether or not to require a minimum service period — for example, six months from the grant date — in order to retain the award. Below are the most common approaches:

- Full RE. Immediate or continued vesting occurs for all unvested shares once the RE conditions are met (including any minimum service requirement)

- Pro rata RE. A portion of unvested shares is earned based on the service provided before retirement relative to the total original vesting life (in our experience, this is most common for performance-based awards)

- Tiered RE. Increasing percentages of unvested shares are earned as stricter conditions are met, such as 50% eligible after 10 years of service, 75% after 15 years of service, and 100% after 20 years of service

Regardless of the approach, providing RE benefits will have downstream financial reporting implications. Focusing on expense, full RE is the most pronounced, with all expense recognized from the grant date to the RE date (when the award is no longer forfeitable). For expense specifically, pro rata RE may not actually require any special adjustments if shares are earned in roughly the same pattern as expense is accrued. On the other hand, tiered RE will likely require custom modeling to accurately reflect each “tier” or breakpoint within each award’s respective vesting. Now let’s layer on the impact of a notice period.

Notice Periods: Overview, Pros, and Cons

As the name suggests, a notice period requires an employee to give notice of their intent to retire prior to actual retirement in order to access favorable vesting provisions. In practice, we typically see notice periods ranging from six months to a year. Notice periods can be combined with any of the RE approaches described above.

To highlight how notice periods work, let’s assume the RE criteria is based on a combination of age and tenure, where an employee needs to be at least 55 years old and have a minimum of 10 years of service. In addition, an employee must provide notice of their intent to retire at least one year in advance.

- Grant date: March 1, 2024

- Employee turns 55: January 1, 2023

- Employee’s 10-year anniversary: February 1, 2024

- Full RE date (later of 55 years old and 10 years of service): February 1, 2024

- Employee provides notice: September 1, 2024

- Employee’s communicated retirement date: September 1, 2025

Since the employee provided notice at least a year in advance, they’ll be entitled to vest in all outstanding equity upon retiring in September 2025. The employee can also choose a date that’s past their retirement date, as long as they provide the required notice.

Pros

Attrition smoothening and load balancing. One inherent problem with retirement-eligibility frameworks that don’t contain notice periods is that every newly eligible employee can leave the day they’re granted new equity awards and create a critical vacancy in the organization. The organization can’t plan for this because it’s unclear who will activate this benefit. Even a one-year minimum vesting period doesn’t solve the problem. Only a notice period mitigates the risk by ensuring managers have a heads-up when someone elects to retire.

Mitigation of spikes in expense. More favorable RE conditions allow for immediate vesting once an employee reaches the RE milestone. This can result in a significant impact to the P&L when the annual grant is issued. This is exacerbated for mature organizations where the employee base has significant tenure because a large portion of expense is recorded on the grant date given no future service is required. Imposing a substantive six-month notice period allows the company to spread the expense over at least two quarters.

FICA taxes. When there’s no longer a risk of forfeiture for time-based restricted shares, FICA taxes are due even if shares aren’t released until a much later date. As such, if an employee is RE and shares are effectively earned, FICA taxes will be due in the year that the RE conditions were met. The same concept applies to any partial RE, though FICA taxes are only due for the portion of the award that’s nonforfeitable. However, if notice of retirement is required, the award is still at risk of forfeiture until the employee has provided notice and satisfied the full notice period. Therefore, pre-vest FICA tax withholdings wouldn’t be required.

Cons

Administrative burdens. Teams will need to track not only an employee’s RE date, but also maintain a database of when an employee provides notice. Internal communication between HR and finance becomes critical since the notice has downstream accounting implications that need to be considered. Some companies consider this a small burden that’s outweighed by the benefits of better, more proactive recruiting and internal mobility strategies.

Employee perception. If you’ve always required a notice period, it’s probably understood and accepted. But introducing one into an existing retirement eligibility framework could be perceived as a detrimental plan revision. Change management becomes extremely important in these cases. One strategy is to roll out the plan provision with a date many years into the future to avoid affecting employees who are on the cusp of becoming retirement eligible.

Expense recognition. As we’ll delve into below, there are a few schools of thought on how expense should be recognized in the event of a notice period. Depending on the method chosen, amortizing awards with a notice period can be challenging.

Do the pros outweigh the cons? We’re not ones to make bold, sweeping statements. But, in general, we think the arguments for a notice period are pretty good and the cons are manageable.

Financial Reporting Implications

Let’s now look at the financial reporting implications of introducing a notice period.

Many plan design changes have an accounting, tax, or disclosure impact. Sometimes these are nonstarters, quickly disqualifying a strategy. Other times, they’re favorable and further support the idea on the table. Then there are impacts that are relatively neutral but nonetheless need to be understood and vetted.

A notice period has a neutral to favorable accounting outcome. The problem is there are competing views on what the accounting should be, making it essential to socialize the intended accounting policy upfront.

As introduced earlier, according to ASC 718, if the legal vest date is non-substantive, the requisite service period ends when the employee can terminate and still vest in the award. Therefore, expense amortization should match when shares are effectively earned and there’s no longer a risk of forfeiture. In the case of continued or accelerated vesting, this is easy. Expense should be recognized from the grant date through the date the employee becomes retirement eligible, which may be the grant date itself.

However, this begs the question: When are shares considered earned when there’s a notice period? There are three schools of thought for the timing of expense:

- The requisite service period should continuously update each reporting period until the employee provides notice or the award vests

- The notice period represents a shorter, fixed requisite service period

- The standard vesting schedule represents the requisite service and is only adjusted when an employee provides notice

Our view is that each of the above has pros and cons. Option 1, while being difficult to implement, is the most technically sound from an accounting perspective. However, given the challenges of implementing it, some companies defer to option 2 to capture what they feel is a substantive term of the award. Option 3 isn’t common, but we share it in the interest of thoroughness because some companies have adopted it.

Option 1: Continuously update the service period each reporting period based on whether the employee has provided notice

This is the most complicated method to account for because it involves updating compensation expense prospectively each period. Most accounting systems can handle retrospective adjustments with cumulative effects in the current period, but amortization models often struggle with prospective kinks in the expense pattern.

Conceptually, the argument is that an employee can provide notice at any time and therefore expense should be recognized over this shortened horizon. However, if an employee hasn’t provided notice in the current period, you keep moving the service end date out each period to account for the notice requirement. Essentially, the minimum service required to vest in the award is elongated every period in which the employee chooses not to give notice. This prospective adjustment is suggested in ASC 718-10-55-78:

If compensation cost is already being attributed over an initially estimated requisite service period and that initially estimated period changes solely because another market, performance, or service condition becomes the basis for the requisite service period, any unrecognized compensation cost at that date of changes shall be recognized prospectively over the revised requisite service period, if any (that is, no cumulative-effect adjustment is recognized).

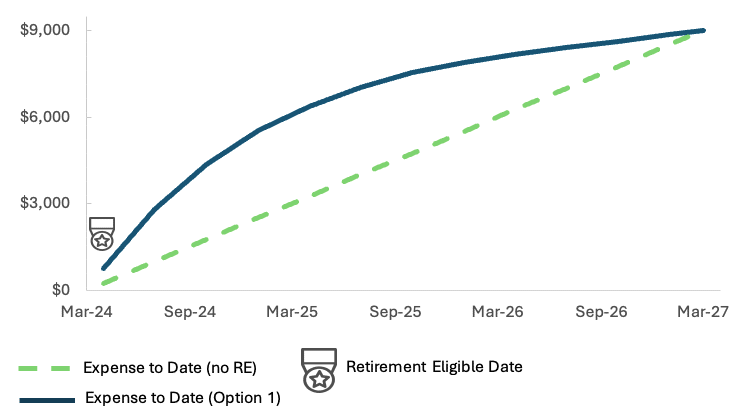

Let’s return to the example above where the grant date is March 1, 2024, and the employee is RE on the grant date. If the employee doesn’t provide notice at the end of Q1, we’ll assume that the remaining expense will be recognized over one year from April 1, 2024 through March 31, 2025. At the end of Q2, if the employee still hasn’t given notice, all unamortized expense at that point will now be pushed out by three months to June 30, 2025—because the new minimum service period to fully vest in the awards now extends through then. This process will continue until the employee provides notice or the vest date is less than one year away. Once the employee provides notice, the expense will be amortized through the communicated retirement date. The graph below represents the difference between an employee who isn’t RE versus an employee who is RE on the grant date, but doesn’t provide notice during the vesting period (Figure 1).

We think this approach is technically sound. That said, it can be cumbersome to implement and difficult to review.

Option 2: Expense the award over the required notice period

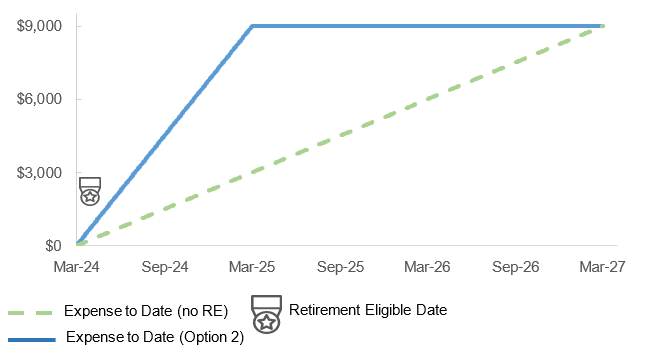

Anecdotally, we’ve seen a number of auditors recommend this approach. The argument is that the initial service period is the notice period, in this case one year, and no further adjustments are needed. As such, expense is recognized over the one-year notice period for an employee who has met the RE rules on the grant date.

Suppose an employee is retirement eligible on the grant date of March 1, 2024 for a three-year cliff vesting award. In this situation, if we were to choose option 2, we would only amortize the award over one year (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Life to Date Expense Under Option 2

This approach is conservative in that expense is recognized more quickly, but it can lead to large reversals later. If an employee retires one year or more into the life of the award but didn’t provide the necessary notice, the unvested shares will forfeit and the full value of the award that was expensed already must be reversed.

Option 3: Adjust the amortization only when an employee provides notice

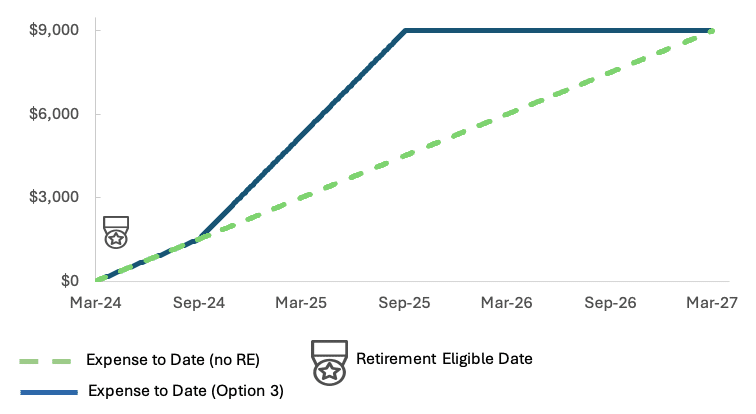

The end of the requisite service period for an award with only a service condition is presumed to be the vesting date unless there’s clear evidence to the contrary. Some companies with a notice requirement argue that the RE provision is nonsubstantive until an employee has declared their intention to retire. Without proper notice, the employee will breach the agreement and surrender their unvested awards. A counterargument is that employees are highly incentivized to provide the necessary notice, which is why this approach is uncommon for companies with material RE populations.

Let’s assume we choose option 3. Using the same dates in our previous examples, we would start by amortizing the award over the three-year period. If the employee provides notice six months into the award, on September 1, 2024, the employee can retain the unvested shares by retiring in one year, on September 1, 2025. In this example, all unamortized expense will be amortized over a 12-month period from the notice date (Figure 3).

Similar to option 1, applying prospective changes to the expense amortization can be extremely challenging for off-the-shelf software or spreadsheet-based processes. We recommend thoroughly testing any solution you choose.

Implementation Considerations

As with all plan design changes, implementing a notice period requires cross-functional communication. Remember to work with accounting, legal, and HR so that all stakeholders are aware of the downstream implications.

Meanwhile, think about how you intend to deal with certain nuances to avoid modification accounting. On its own, implementing a notice period (or any RE provision, for that matter) typically isn’t a substantive modification, but your plan should reflect what you decide to avoid confusion.

Departure prior to notice period end date. If an employee provides the required notice, but a succession plan is put into place before the notice period end date, can they leave early and still retain their awards? Using our example, the employee communicated that they would retire on September 1, 2025. However, as of March, a full succession plan was already in place. If the company and employee both agree to an early retirement, this would constitute a modification if not articulated in the award agreements. We’ve found that best-in-class award agreements contemplate an early, mutual departure that allows for award retention in these cases. The financial implication here is that an acceleration of all unamortized expense will occur on the new departure date, versus being amortized through the original notice period end date.

Future grant cycles. Will employees be eligible to receive any new equity awards? For longer notice periods, where notice has already been provided after the annual grant cycle but the employee will still be employed during the upcoming cycle, we typically don’t see additional grants being issued. However, we’ve seen exceptions made for executives and employee-specific negotiations. Regardless, it’s unlikely companies will want to issue a new award that would be forfeited upon the employee’s departure given the retirement is a known event.

Prospective versus retrospective addition of a notice period. Once a notice period is decided on, should this change be implemented prospectively or be applied to existing awards? When we see notice periods newly implemented, it is prospectively. Applying this to existing awards could be viewed negatively by employees, especially those who are already retirement eligible and perhaps contemplating providing a customarily shorter amount of notice.

Maximum allowed notice. In theory, a new hire out of college could provide notice of their intent to retire in 30 years. Practically speaking, employees are unlikely to provide more notice than is required, but it’s possible. Employees should at least be able to provide notice one year before they reach full RE (using our same example). For someone who already reached full RE, if they provide 18 months’ notice but then retire after 12 months (again, the required notice), they would presumably retain unvested awards as long as the early departure is mutually agreed-upon.

Aligning Retirement Provisions with Company Goals

Retirement eligibility can be an enticing benefit—both to attract talent in the first place and by retaining experienced employees. But RE also has costs that can discourage companies from offering it or maintaining it as the number of tenured employees grows.

One way to address some of the drawbacks is to require a notice period to qualify for favorable retirement treatment. There are pros and cons to this strategy, as well as policy details to clarify and discuss upfront. However, the pros can be compelling from the company’s standpoint and the additional administration complexity is manageable with the right advisors and technology.

When contemplating a notice period, always start by modeling the implications from multiple angles. How will compensation expense change, holding other factors constant? How will employee behavior change? What sort of change management would be communicated to current employees? These and related questions will help your cross-functional team consider the full ramifications of this potentially strategic award design change.

If you’d like to know more about notice periods in the context of your own company’s retirement eligibility plan, please get in touch.