Options Backdating 2.0? The Timing of News Releases around Option Grants

The option backdating scandals of the 2000s were initially unearthed through an academic research study. As we helped companies work through backdating issues, we found that a majority of the cases were linked to weak controls and not malpractice (with notable exceptions, of course). For these reasons, we took notice of a recent article in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis by Robert Daines, Grant McQueen, and Robert Schonlau. They argue that companies are now using creatively-timed information releases to manipulate option compensation for their executives.

We believe this research is worth knowing about because if even a few companies are found to be doing this, it could result in all companies facing heavier scrutiny of their disclosures. Similarly, it’s quite possible that overly simple or incomplete processes may give the semblance of this occurring when in reality there’s no negative intent. We’re raising this as a potential issue in the spirit of helping our clients stay ahead of the curve and continuously upgrade their controls.

We’ll get to the specifics of those new findings in a minute. First, let’s review what happened with options backdating that caused the SEC to take action before.

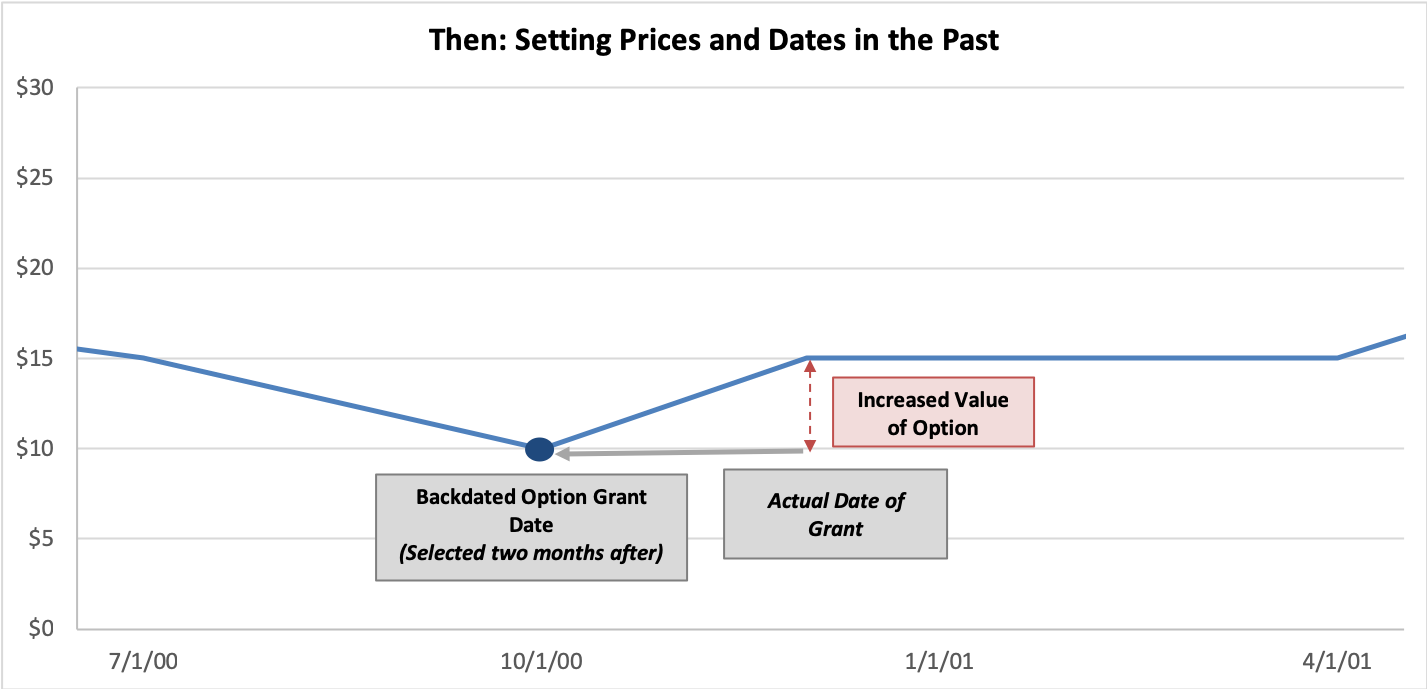

Then: Setting Prices and Dates in the Past

In the 1990s, it became common for companies to backdate the options they granted to their executives. Because companies had two months to disclose their grants, executives would look backward for a date when their company’s stock has its lowest trading price, then assign this particular date as the option grant date. That way, executives could receive a grant below the current market price while investors may have believed that the grant was at the money. Options backdating also enabled companies to issue enormous compensation packages to executives without notifying shareholders, and allowed executives to claim certain IRS tax advantages ordinarily reserved for options granted at the money.

In December 2001, the company’s stock price has been increasing. They look backward two months and assign October 1, 2000 as the grant date since the stock price was the lowest at this date.

However, this scheme caught the eye of regulators. The SEC began a thorough investigation in 2006, ending in a long string of criminal charges and executive resignations. Regulatory issues aside, when we helped dozens of companies through a backdating analysis, we found numerous cases in which grant dates were chosen randomly. This lack of process led to employees being worse off than had the best practice been followed.

The resolution was to require new grants to be disclosed within two business days, making the long lookback required to backdate an impossibility. Today, most companies schedule their option grants well in advance and on a predetermined date.

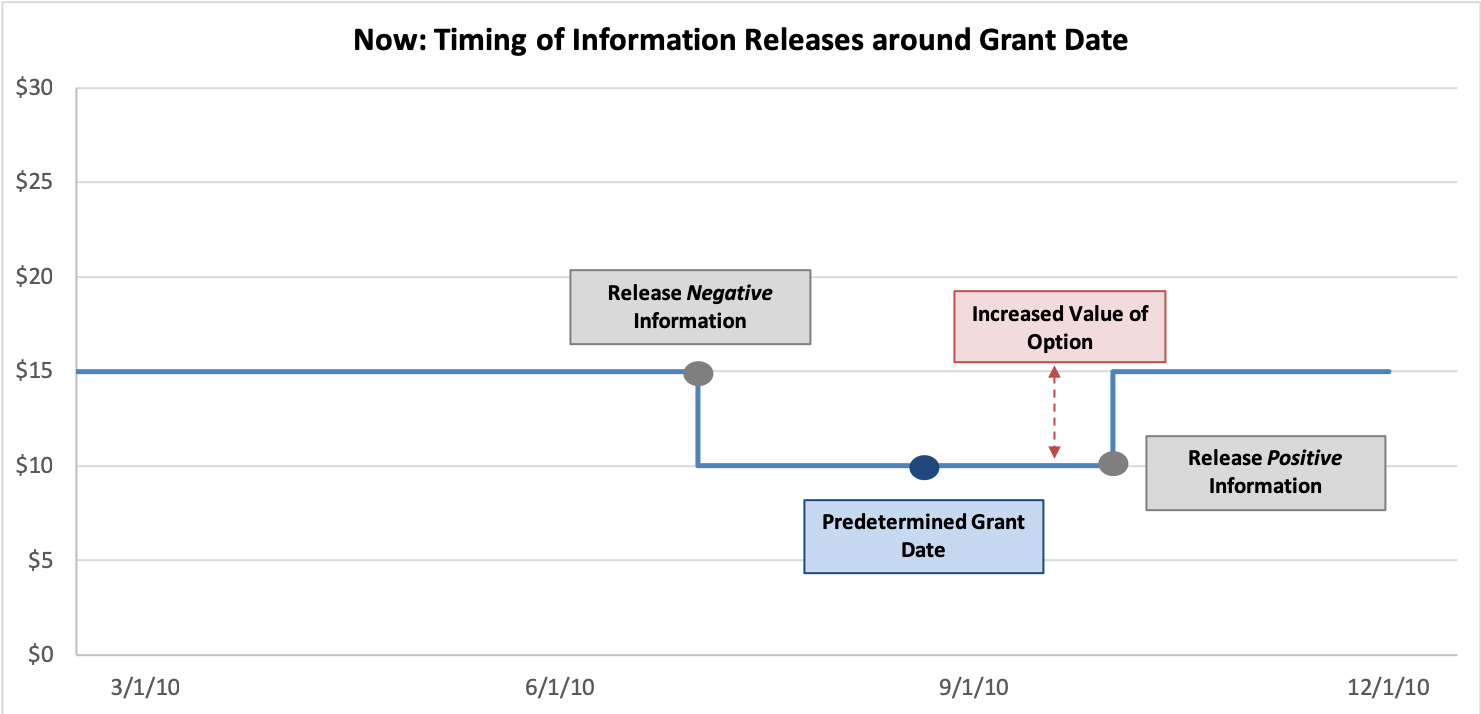

Now: Timing of Information Releases around Grant Date

Daines and his colleagues report evidence of significant abnormal price movements around scheduled CEO option grant dates after 2006. The evidence is a significant V-shaped pattern in the stock price among a group of more than a thousand companies. Before the option grants, companies’ stock price trended lower and stayed low on the grant date. Soon after granting the options, stocks tended to rebound.

Specifically, their analysis estimates an average abnormal negative return of 1.9% in the 90 days before the option grants, and an average abnormal positive return of 1.1% afterward.

At the same time, the researchers find evidence of more negative 8-K releases before option grants and more positive 8-K releases after option dates, as measured by stock price response to the news. The disclosure timing appears to have been adjusted two ways:

- Bullet dodging. Before the grant date, the company releases news that can negatively impact the stock price.

- Spring loading. After the grant date, the company releases news that can positively impact the stock price.

In some cases, the timing appears to involve the use of discretion over actual earnings or accruals to increase stock option compensation. For example, companies might aggressively report cost amortizations before the grant date or postpone announcing positive strategies until after the grant date.

Additionally, the researchers report that the data yielded a stronger stock price pattern for larger option grants to the CEO. The more influence a news release had on the stock price, the more significant the V-shaped stock price pattern appears to be.

The company is scheduled to grant options on September 1, 2010. The company elects to provide more negative news prior to the grant date, pushing the stock price down, and positive news after the grant date, causing the price to recover.

How Will This Play Out?

We find this new evidence a little surprising, as current regulatory enforcement and public scrutiny are very strict regarding options compensation. Information releases that are timed to influence the stock price affect more than just executive compensation. They also affect months’ worth of gains and losses for investors.

It’s also worth noting that the original backdating scandal began after an academic, Erik Lie, published a similar study of anomalous returns before and after option grants attributing this to backdating. In fact, Lie notes that David Yermack of NYU also detected the pattern in research published in 1997, but the pattern was attributed to expectations of price increases, not backdating. It took quite a while for the fallout to occur after the results were first disclosed in 2004. But when it did, the result was a large number of investigations, restatements, and even some prison sentences.

In our experience working with executives, they have a lot more on their minds than a few upcoming equity award grants. Nevertheless, if history is at all predictive, these early warning bells are worth examining if just to improve overall granting practices. Take a moment to review the timing of your firm’s information disclosures to ensure they can’t be misconstrued in a way that could draw unwelcome attention.