The Latest on Tax Reform and Equity Compensation

Just in time for the new year, President Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which presents the most sweeping changes to the tax code in decades. A few weeks ago, we had looked into some of the anticipated changes to equity compensation. Now that the rules are final, there’s much more to discuss.

True-Down of Deferred Tax Assets

SEC Guidance on Computing DTA Adjustments

IRS Section 162(m)

Qualified Equity Grants (for Private Companies)

True-Down of Deferred Tax Assets

Perhaps the most consequential change of tax reform is the lowering of the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%.[1] In the short term, this will result in a major true-down of the deferred tax asset (DTA) on companies’ books for equity compensation, which will in turn worsen earnings for the reporting period in which the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was enacted. (Thereafter, DTAs and the corresponding tax benefits will be smaller. But, of course, that’s because corporate taxes will be lower.)

DTAs in Brief

Compensation expense is calculated and allocated differently under GAAP than it is under tax rules. This leaves companies with a reconciliation problem between the expense they show in their financials and the eventual deduction they take in their tax returns. To address this, accounting rules require setting up a DTA based on the cumulative book expense for awards that are expected to result in future tax deductions. Once awards are settled and give rise to a taxable event, the DTA must be reversed.

The DTA represents a future deductible amount that will produce tax savings at a later date. At the same time the DTA is recorded, a deferred tax benefit is recorded in the income statement, which reduces current period tax expense. At the close of each reporting period, the balance in the DTA should be equal to the cumulative recorded compensation cost for outstanding awards multiplied by the appropriate corporate tax rate.

A reduction to the carrying value of the DTA increases income tax expense because it represents the impairment of a future expected tax benefit.

For more about the tax implications of equity awards, see our white paper on the topic.

For example, suppose Company ABC grants 1,000 restricted stock units (RSUs) on January 1, 2016 at a market price of $15, and will cliff-vest on December 31, 2018. There is no forfeiture rate. For the following calculations, assuming the statutory tax rate is 35% and the company’s fiscal year ends on December 31.

- Total compensation cost will be $15,000 (1,000 x $15), which will be recorded evenly over 2016, 2017, and 2018.

- As compensation cost is recorded, Company ABC records a DTA to the balance sheet and a deferred tax benefit reduces tax expense in the income statement. By the end of the vesting period, the balance sheet should contain a DTA of $5,250 ($15,000 x 35%).

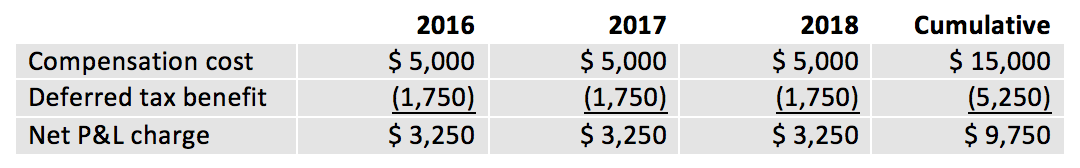

The income statement will reflect the net charges in Table 1.

Table 1: Net Charges to Earnings Prior to Tax Reform

When these RSUs vest, the tax deduction will be considerably smaller as a result of tax reform, despite the uptick in the stock price. To illustrate, suppose that at settlement, the stock price has spiked to $25. Now the company can deduct only 21% of $25,000 (1,000 x $25) instead of 35%. The smaller future tax deduction means there is an inflated tax savings being projected in the financials that functionally needs to be “impaired,” thereby reducing the deferred tax benefit and increasing tax expense in the period of enactment.

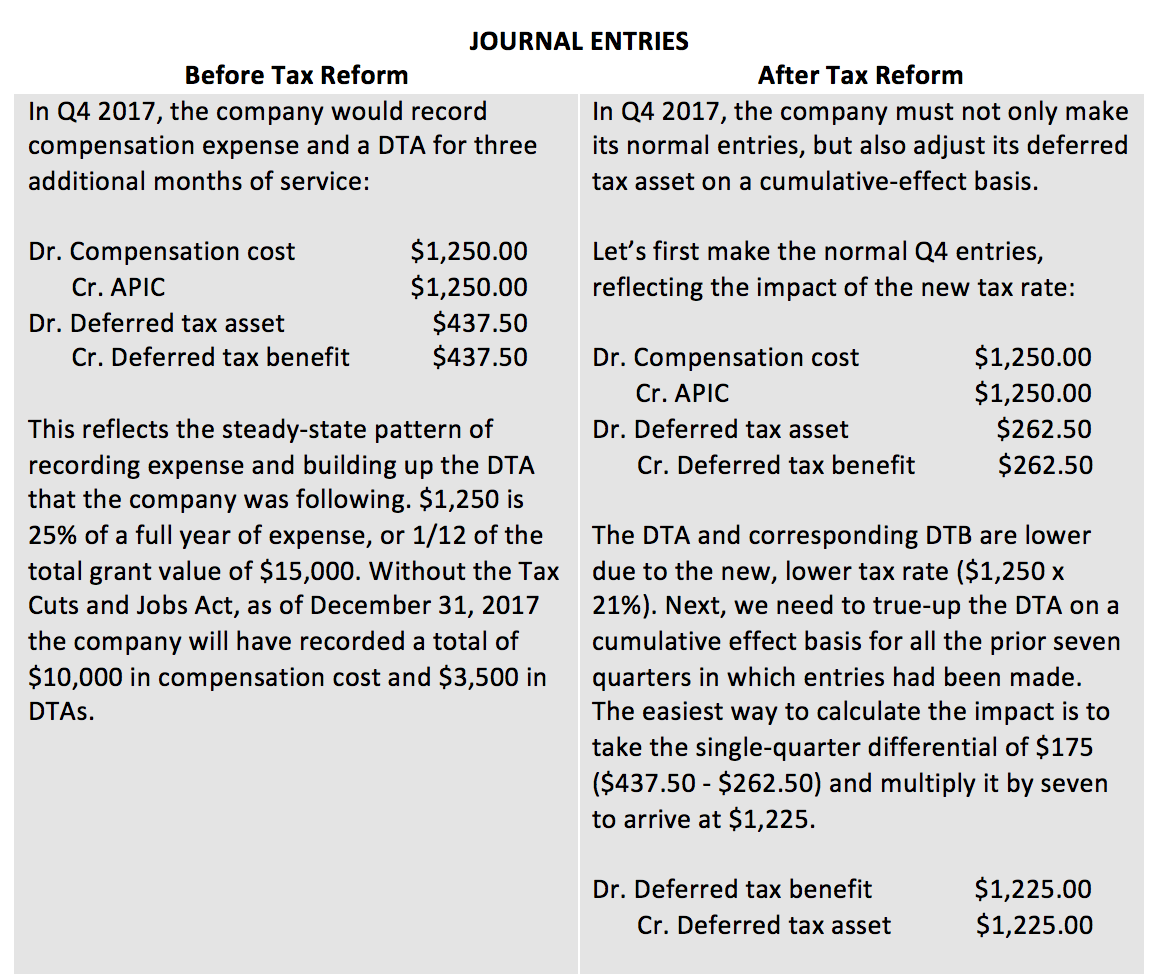

To make the mechanics more tangible, let’s look at what the Q4 2017 journal entries would be had the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act not gone into effect in December 2017, then compare that with the journal entries that are now required. This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Journal Entries Prior to and After Tax Reform

We write down the DTA by crediting it $1,225. The offsetting entry is a debit of the same amount to deferred tax benefit (DTB), which increases income tax expense and decreases net income. Playing it all the way through, the net effect is an increase to the tax provision (income tax expense) and a reduction to net income.

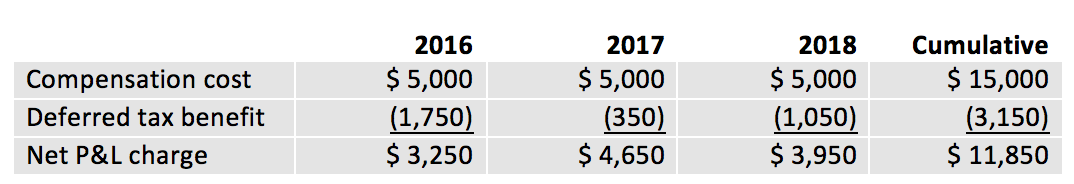

Returning to Company ABC’s example, Table 3 shows how the net charge to earnings in 2017 and 2018 will be higher, assuming the statutory tax rate becomes 21% in 2017.

Table 3: Net Charges to Earnings Post-Tax Reform

This has considerable financial statement implications. Thinking holistically about all the factors giving rise to temporary differences, companies with a net DTA balance (i.e., they have more deferred tax assets than deferred tax liabilities) will see an increase in their tax provisions (since the value of their tax benefits has decreased). A higher income tax expense means lower net earnings, holding all else equal. However, in the future, actual income taxes payable will be lower due to the lower tax rate. That means the company will write a significantly smaller check to the IRS for the same amount of taxable income as they would have under the old tax code.

The long-term impact of tax reform—lower taxes—is clear. But in the short term, there are two dangerous consequences.

Missed performance metrics. Tax reform may cause firms to artificially miss or exceed performance metrics on outstanding equity awards. Why? Because firms issued them in anticipation of an earnings flow that included tax deductions at the prior higher rate. The tax bill worsens net income for companies in a net DTA position and enhances net income for firms in a net DTL position. Operating performance is unchanged, but depending on your firm’s situation, you may experience an artificial headwind or tailwind on your performance metrics.

The standard solution for something this significant is to revise performance targets to adjust for the increase or decrease to income tax expense that’s linked back to tax reform. But measure twice and cut once: Be sure to carefully review your award agreements to ensure this can be done and vet the process carefully with your compensation committee.

Financial volatility. For the same reason, as-reported GAAP earnings will experience considerable volatility in the financial reporting period that includes December 2017. As companies true-down their DTAs and incur an uptick in their income tax expense, as-reported net income will decline (or, for those in a net DTL situation, as-reported net income will improve). We expect that non-GAAP disclosures will be needed to explain why the reported GAAP financials fell out as they did.

Remember, equity compensation is just one piece of an overall puzzle. Since some firms are in net DTA positions and others are in net DTL positions, overall comparability among companies will worsen. For this reason, be sure to understand not only how your financials are affected, but also those of your peers. If you’re in a net DTA position and experience erosion in net income, but your peers benefit through a tailwind to net income, you’ll need to carefully prep stakeholders on how the different moving parts are interacting.

SEC Guidance on Computing DTA Adjustments

Under ASC 740-10-45-15, changes in tax law must be recognized in the period the new legislation is signed into law—which, for our purposes, is 2017. Shortly after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act became law, the SEC introduced Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 118 (SAB 118). This new guidance is intended to help companies decide how their 2017 financials should reflect the new tax regime.

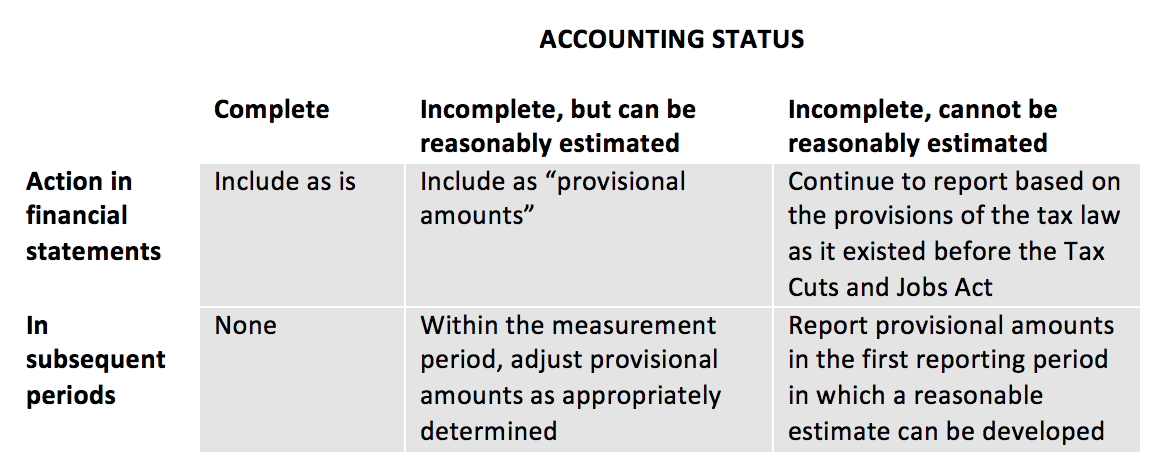

SAB 118 acknowledges that some organizations might not be able to complete all their accounting for the tax bill’s income tax effects before it’s time to close their 2017 financial statements. If that’s the case, according to the SEC, companies can develop a reasonable estimate of those income tax effects and report this in their financial statements as a provisional amount. If a reasonable estimate isn’t feasible, then companies should continue to apply ASC 740 based on tax law prior to the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. In short, there are three layers of information, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Treatment of Tax Reform’s Income Tax Effects

This flexibility is offered for a limited time, or measurement period. That time should not exceed one year from the reporting period in which the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was enacted.

For most companies, the equity compensation implications of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act should be relatively straightforward to compute (or at least reasonably estimate).

On a related note, some have asked whether DTA changes stemming from tax reform trigger an 8-K filing responsibility. The SEC says no. According to Compliance & Disclosure Interpretation 10.02, remeasurement of the DTA does not trigger an obligation to file under Item 2.06 of Form 8-K unless the new tax laws suggest the DTA may no longer be realized.

IRS Section 162(m)

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Internal Revenue Code Section 162(m) capped at $1 million the tax deductions available on non-performance-based compensation to the top four executives. (The top four generally were the CEO and next three highest-paid executive officers, excluding the CFO.) Performance-based awards meeting specific criteria were fully deductible.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act radically changes these rules:

- The exclusion for performance-based compensation is gone. This means that, of all compensation paid to “covered employees,” the portion in excess of $1 million is no longer deductible even if it’s performance-based.

- Covered employees now include the CFO.

- Once an employee is covered by the rule, he or she is always covered. This prevents companies from delaying payout to a current executive until that executive takes on a smaller, pre-retirement role.

- More companies are subject to the rule, including public debt issuers and foreign private issuers.

A central question is how to handle outstanding equity awards under the rule. The final bill grandfathers in compensation that is “pursuant to a written binding contract which was in effect on November 2, 2017, and which was not modified in any material respect on or after such date.”

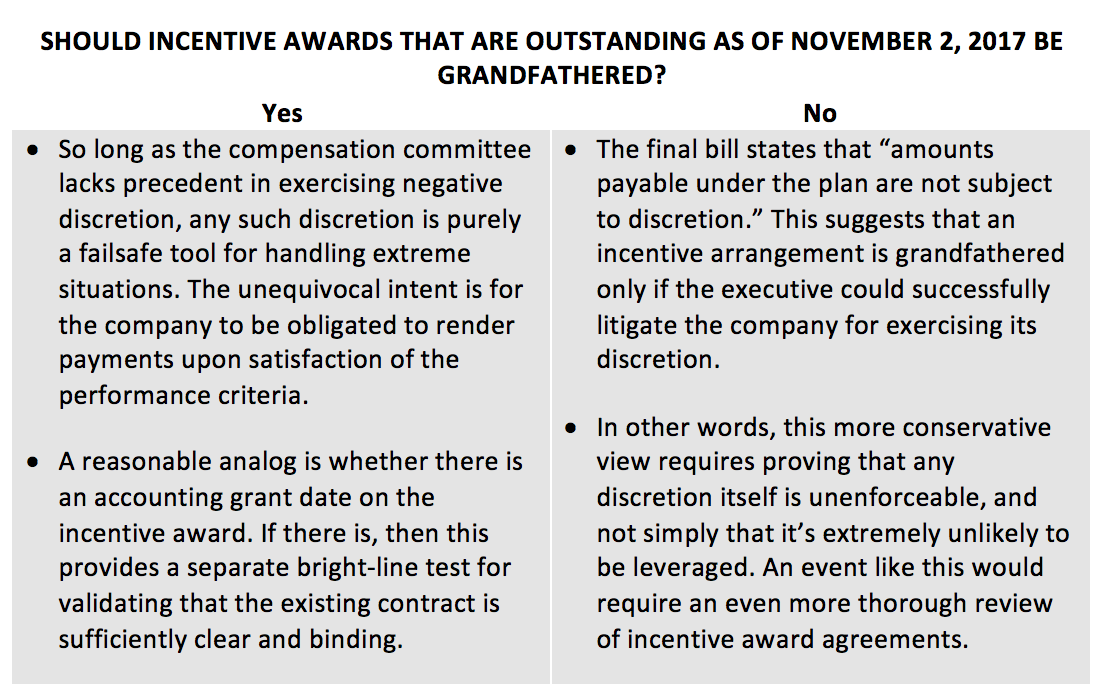

However, this doesn’t clarify exactly what’s covered, given that most annual bonus programs and long-term incentive awards give the compensation committee negative discretion to reduce or eliminate payments. As of early January 2018, opinions among compensation attorneys vary. Table 5 shows both sides of the debate.

Table 5: The Debate on Grandfathering Outstanding Incentive Awards

Going forward, the compensation paid to covered employees in excess of $1 million will not be tax deductible even if the excess portion is performance-based, thereby creating a permanent difference between book and tax rules. Compensation cost will be recorded on these awards but a DTA will not be recorded.

While the tax deductibility of executive compensation arrangements will be missed, there is a silver lining. Compensation committees went through elaborate gymnastics to draft incentive designs that were 162(m)-compliant, often sacrificing the design they really wanted for one that was tax deductible. Going forward, this maneuvering will no longer be necessary.

Qualified Equity Grants (for Private Companies)

Equity award recipients at private companies famously run into major liquidity problems. Without creative and sophisticated arrangements, there’s usually only one way to exercise vested stock options: Pay the strike price. That satisfies tax withholding responsibilities, but requires recipients to go out of pocket. Most employees therefore choose to hold on to their options, only to potentially forfeit them if they leave the company prior to a liquidity event.

Dash Victor describes one solution popular among high-tech firms. It extends the post-termination exercise window so that terminating employees can retain their awards and the opportunity to participate in future upside.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act introduces a new Section 83(i) giving private-company employees another way to participate in value creation outside of a liquidity event. Under this provision, companies can issue qualified equity grants that let the employee defer taxation on vesting RSUs or stock options up to five years.

To qualify, the plan must encompass at least 80% of all full-time US employees and deliver the same rights and privileges (though not the same grant sizes). Certain senior employees are excluded from being able to participate. To affirmatively select this deferral option and notify their employer, employees have 30 days following the earlier of the vesting date and when the award becomes transferrable. The downside is that after five years, the tax liability is due, and it’s possible that value will have declined. While the language in the final rule is not entirely clear, we interpret the rule as purely pushing out when the tax is due (but not the tax basis itself).

This means the tax liability is still tied to the spread at exercise. Employees are therefore motivated to hold vested options as long as possible. Terminating employees will face the tough decision of whether to exercise, make the deferral, and then hope that the illiquid security becomes liquid over the next five years. In short, this provision gives employees in private companies more choice, but it doesn’t alleviate the inherent risk of dry income.

Tax-Exempt Organizations

Tax-exempt organizations will continue to incur excise taxes on highly-compensated individuals.

Today, under 280G rules, tax-exempt organizations that pay any employee more than $1 million a year must either pay an excise tax or trigger “excess parachute payments.”

Tax-exempt organizations have long come under fire over executive compensation. But large nonprofit entities often recruit executives from the public markets. As a result, they’re under pressure to match or approach the recruits’ current compensation levels. For better or for worse, this provision keeps the compensation schemes of large tax-exempt organizations under the critical scrutiny of potential donors.

Questions about this article? Please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Contact Us

———————————————————————————————————————

[1] Although the statutory tax rate isn’t what many companies end up actually paying in taxes (due to various deductions, credits, and other tax optimization tools), for now we’ll assume it is.