Getting the Conversation Started on Pay Equity Remediation

Over the last several years, employers went from aggressively raising pay by orders of magnitude to hitting the brakes in response to cost pressures. Swings like this can leave unintended disparities in their wake as hiring decisions, counteroffers, and ad hoc pay adjustments accumulate over time.

Pay equity studies give talent leaders an apolitical way to make sense of all the movement and complexity in pay decision-making. They’re also an important input to the annual merit process because they help guide decision-making and keep small problems from getting bigger. Done right, pay equity studies sidestep the ESG political football to test one basic thing: Is there evidence of pay decisions being linked to inappropriate factors that are wholly detached from the compensation strategy?

Even so, one of the principal challenges in running a pay equity study is translating the findings into action. We’ve met many CEOs, CFOs, and board members who worry that a pay equity study will lock them into taking financially untenable steps. This concern is unfounded.

Remember that a pay equity study is a modeling exercise designed to identify any areas that need further examination from the compensation team. The larger the company, the more hidden these areas are likely to be. That’s why we use models. There’s no “gotcha” dimension to them. They’re simply tools to support decision-making.

In the same way a cybersecurity department would never publish all the inner workings of its network penetration tests, pay equity studies are typically conducted under legal privilege for the company’s own benefit. The aim is to ensure comfort with how on-the-ground decisions are being made.

In the rest of this article, we’ll share some highlights and governing principles on how the remediation phase typically goes down. Whether this is the first year you’re planning to perform a pay equity study and are wondering what the remediation might look like, or you’ve been performing this analysis for many years and are seeking a remediation strategy that best fits your goals, we hope these insights demystify the process and help you address pay disparities head on.

Equity Methods has published extensively about pay equity studies, exploring topics from the intricacies of its statistical analysis to the interaction of external labor market conditions and internal pay dynamics. But when it comes to why companies run pay equity studies, the reasons are pretty basic:

- Regulatory compliance

- Talent retention

- Litigation avoidance

- Active litigation defense

- Alignment with meritocratic and transparent compensation practices

- Strategic talent assessments related to the compensation strategy in action

In short, a pay equity study is simply another decision support tool. To enable full and frank discussions, pay equity studies should be done under legal privilege.

Overview of Key Findings From a Pay Equity Analysis

An effective remediation plan is guided by the findings of a properly executed pay equity analysis, which considers the effect of legitimate compensation drivers in the measure of pay discrepancies across gender and racial groups. The analysis must also account for the job architecture in an organization, or risk comparing pay among individuals with different levels of responsibility, expectations, and oversight.

The gold standard in conducting a pay analysis is a linear regression model. By placing employees in accurate job buckets and accounting for allowable factors, the regression model simulates the expected differences in pay across individuals who are similar to each other in all other aspects except gender, race, and any other protected class status.

It’s important to take into account the applicable legal framework when performing a pay equity audit. In many US states, the standard is “equal pay for substantially similar work,” while in Canada and the European Union, legislation uses the framework of “equal pay for equal value.” The legal backdrop impacts how employees should be organized and what factors can be used in the regression modeling.

There are two outcomes from a pay equity analysis that help us design the remediation plan: pay gap(s) and employee-level predicted pay range.

Pay Gap(s)

Ideally, organizations should aim to have 0% difference in pay among comparable employees of any gender, race, or other protected class. More commonly, however, the regression model in a pay equity analysis finds asymmetries in pay across members of different classes. For example, the model might find a negative female gap of 5.0% and a positive Asian gap of 2.0%. This means that, all else being equal, women are paid $95 for every $100 earned by comparable male colleagues, and Asians are paid $102 for every $100 earned by comparable White employees.

Pay gaps can be further divided into two types:

Firm-level pay gaps. These are gaps estimated from the entire employee population of a company, i.e., they measure disparities at the level of the organization as a whole.

Cohort-level pay gaps. These gaps measure disparity among classes in sub-segments of the employee population as if they were entirely separate entities, i.e., a pay equity analysis is performed for each relevant sub-group of the employee population.[1]

For example, a cohort-level analysis might reveal that pay is equitable among male and female junior associates, while gender disparities arise in the manager cohort. Cohort pay gaps help us direct remediation resources more efficiently by uncovering pockets of inequity otherwise invisible at the level of the whole company.

Employee-Level Predicted Pay Range

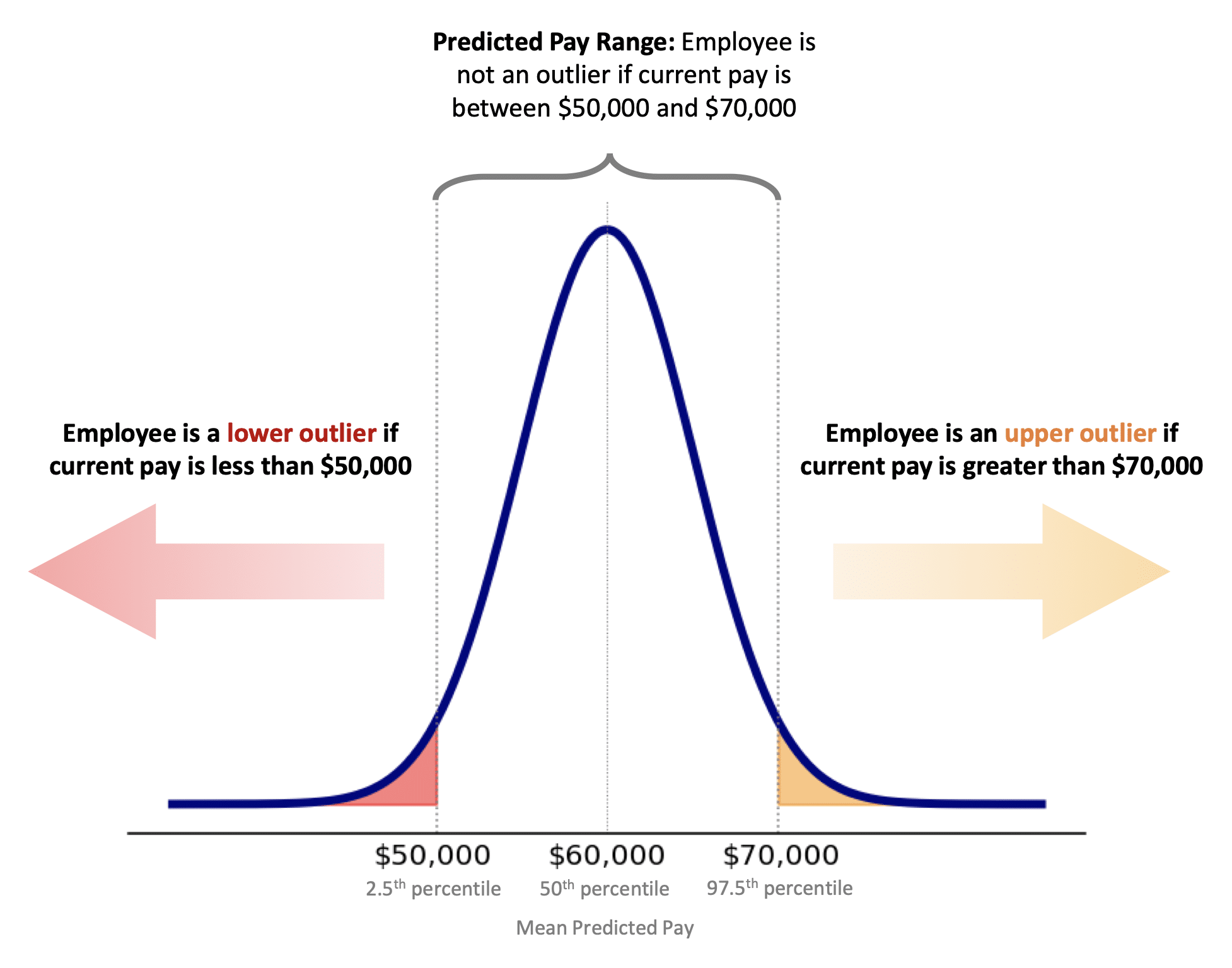

Besides showing us pay gaps, the regression model determines the minimum and maximum compensation that employees are expected to earn based on their attributes (e.g., role, location, experience, performance, certifications, book of business) and the company’s pay philosophy. The range of values between the minimum and maximum values is referred to as the individual predicted pay range. For example, a senior sales associate with a five-year tenure in the Midwest branch of XYZ, Inc. is expected to earn between $50,000 and $70,000 annually.

The pay prediction interval for each employee will show which individuals are falling below their predicted pay range. Addressing such cases is a good start in achieving overall pay equity as part of a remediation plan.

Identifying Outliers

Employees whose current pay falls outside of the predicted pay range are called outliers. Outliers are then classified as either lower or upper outliers, depending on whether their pay is below the lower limit or above the upper limit of the individual predicted pay range.

To understand how to identify outliers, suppose we’re interested in the predicted pay range of an employee with five years of experience. The regression model finds that for this individual, the expected pay is $60,000, and anything between $50,000 and $70,000 is within acceptable bounds.

Pay close attention to the term “acceptable.” It’s a technical aspect of pay equity studies that has great importance, both for the statistical analysis and in the context of labor and employment litigation.

There are many factors associated with pay that HR records capture perfectly, no matter how sophisticated talent management capabilities are. For example, communication skills, productivity, openness to new opportunities, and grit are all gender neutral and expected to drive compensation differences. However, these factors are rarely captured in the data.[2]

This implies that the predicted pay has a certain level of uncertainty. The most commonly used level of uncertainty admitted in the social sciences literature and courts is the 5% level, also referred to as the “two standard deviation rule.” It’s on this value that pay ranges are set.

When compensation falls outside the bounds established by the rule, we say that it’s unlikely to be driven by the omitted factors—or, equivalently, that it’s beyond reasonable doubt that the employee’s pay is below or above that of comparable colleagues.

Remediation Strategies

If an audit reveals pay disparities in the organization, the next step is to understand the potential ways to resolve the issue.

Crafting an appropriate remediation strategy is one of the most bespoke and subjective steps of the pay equity analysis. It calls for a blend of technical expertise from the statistical consultants and ongoing, collaborative discussion with key stakeholders from the legal and compensation teams.

Said differently, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Closing the pay gaps must be balanced with the organization’s compensation philosophy, business objectives, and budget or resource constraints. As such, we suggest designing a plan based on the company-specific outcomes of the pay equity analysis and tailoring from there.

With that in mind, here are three foundational strategies to help anchor the discussion around remediation.

Remediation Approach #1: Remediate Lower Outliers From the Ground Up

Correcting the compensation of lower outliers is a good first step in remediation if a valid reason cannot be found to explain their pay levels, because these individuals pose the highest retention and legal risk.

If a pay equity audit found no large or statistically significant pay gaps within the organization or individual cohorts, then adjusting the pay of lower outliers would be sufficient remediation, as there are no more widely observed pay disparities to close.

What if the audit finds pay disparities? Can the pay gaps be completely closed by adjusting the pay of lower outliers? Not necessarily. It’s more common than not to find employees of both protected and baseline groups among the lower outliers.

In an organization with a negative female gap of 4%, for example, it’s very likely that there are more women among lower outliers. But it’s almost certain that some men will also be present. In this scenario, adjusting the pay of lower outliers will improve the overall situation of female employees, but will also move the goalposts as some men will have their pay adjusted upward.

Companies in this situation should consider prioritizing adjustments to chronically underpaid individuals in order to maximize budgetary impact. Otherwise, you should consider other measures, including the next two approaches.

Remediation Approach #2: Adjust Disparities Beyond Outliers

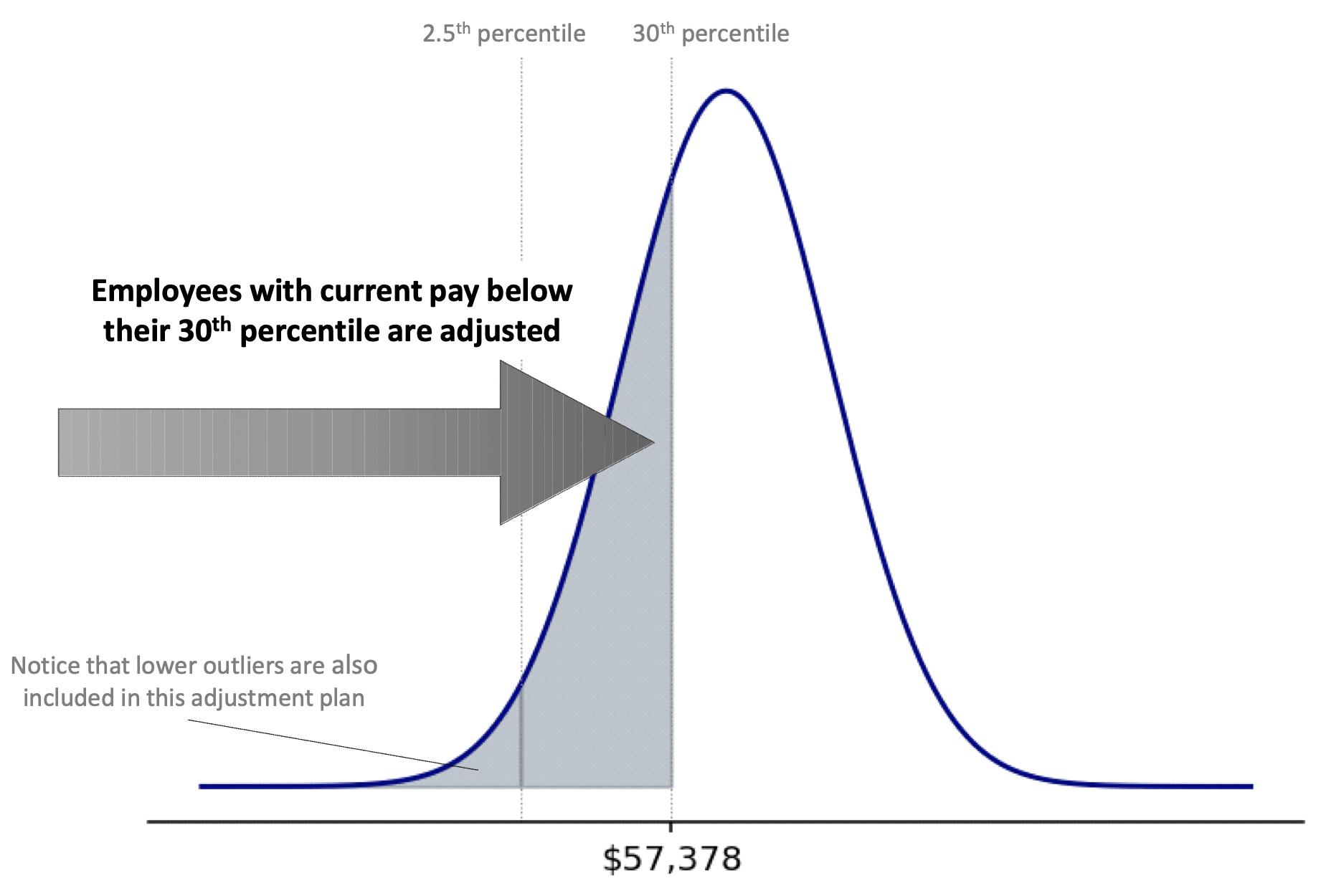

In most cases, closing the pay gap will involve adjusting payments for employees who don’t fit the definition of outliers but are still underpaid relative to the target pay predicted by the regression model. To identify these employees, we rely on the predicted pay range, looking at thresholds above the lower bound used to classify lower outliers. In other words, we increase the threshold to flag employees as outliers.

The predicted pay range is the distribution of pay for any employee with given attributes based on the available data. Lower outliers are those that are in the bottom 2.5% of this distribution, according to the threshold most commonly adopted in the statistical literature. But we can use the same range to explore how pay gaps turn out when we apply adjustments to individuals in the bottom 5%, 10%, 20%, and so on.

As with lower outliers, larger shares of protected group employees will be found in the bottom X% of the distribution (where X is greater than or equal to 2.5) relative to the baseline group when there’s a pay gap between them. This suggests that adjusting the pay of employees in the bottom 30% of their prediction interval will help decrease pay gaps. However, the organization determines what the remediation percentile will be.

Building on the example we used for identifying outliers, let’s assume that employees in the bottom 30% of their predicted pay range make up to $57,378 in annual salary. Adjusting every employee in the bottom 30% up to $57,378 closes disparities among lower outliers and among employees between the 2.5th and 30th percentiles of the pay distribution.

Whether using the 30% mark will be enough to close pay gaps varies case by case. We’ve had clients for whom adjusting employees in the bottom 30% region of their predicted pay was more than enough, which allowed for a reduction in scope and cost of the plan. For others, more aggressive plans were needed, where we had to evaluate remediation based on percentiles above the 30th percentile. Regardless of which percentile companies decide to proceed with, it’s essential that pay equity providers provide precise information about the cost and projected gaps embedded in the proposed plans.

Remediation Approach #3: Use a Remediation Investment Optimization (RIO) Process to Close Pay Gaps

If the pay equity audit reveals a firm-level pay gap for a certain demographic group, looking at lower outliers is a necessary but insufficient step to meaningfully reduce that gap. You’ll need a broader remediation strategy that’s mindful of budget constraints.

Suppose a 4% pay gap is observed for a demographic group with a total annual payroll of $10 million, implying an aggregate dollar gap of $400,000. Blending statistical expertise, your compensation philosophy, and the data, we can configure a model that optimally allocates remediation dollars across individuals to cost-effectively create maximum impact on closing the gap. For example, a remediation plan can be executed to achieve the desired objective of closing the $400,000 gap while only costing $200,000.

Our remediation investment optimization plan aims to maximize the return on pay equity investment by prioritizing adjustments to individuals with the highest impact on the calculation of this average.

While we have algorithms that can do the computational heavy lifting, human decision-making is critical to ensure that outcomes make sense in the context of a company’s compensation philosophy. Reasonable parameters must also be developed based on what makes sense for a particular organization (e.g., by imposing a restriction that the maximum pay adjustment cannot exceed more than 5% of an individual’s total compensation).

Case Study: Customizing Remediation Approaches Based on the Analysis Outcome

Each organization’s pay equity audit results, target objectives, and resource constraints vary. As such, the remediation approach for each needs to be customized to their individual situations.

Let’s use a simple case study to illustrate. In this hypothetical example, the audit findings for three firms show identical results. That is, there’s a 2% gender pay gap for the organization overall, and four out of 20 employee cohorts have 5% gender pay gaps (two favoring males and two favoring females).

For Firm #1, this is the first year that they’ve performed a pay equity audit and didn’t have the budget available to resolve the issue. In this case, the best approach would be to proceed slowly and focus on reviewing the lower outliers to determine if there are valid factors that explain their lower pay relative to colleagues. For those for whom no such valid explanation is identified, the compensation team at Firm #1 would work with the relevant managers to prioritize more of the annual merit budget to adjust the pay of lower outliers in the next cycle.

The company also flagged upper outliers whose pay amounts, in many cases, exceeded the maximum compensation guidelines for their level and considered reducing the annual increase for certain individuals.

Firm #2 is focused on ensuring that no cohorts have large pay gaps, any pay adjustments are doled out in a simple and transparent manner, and the remediation approach doesn’t create “leapfrogging” issues. However, pay adjustments for only the lower outliers won’t close the gaps for individual cohorts.

The analysis shows that increasing the pay of employees in the bottom 10th percentile of the four problematic cohorts would close the observed gaps. This remediation plan, which is different from Firm #1, would work best to meet Firm #2’s objectives.

Finally, Firm #3 has performed a pay equity audit for the past four years, applying a similar approach as Firm #2, but the overall gender pay gap of 2% is persistent. This year, Firm #3’s new CEO challenged the compensation team to find a way to close the pay gap and provided a larger budget than in prior years.

In this case, the optimal strategy would be to remediate lower outliers and implement the RIO process, providing differentiated pay adjustments to certain employees with the aim of closing the gender pay gap for each of the cohorts, as well as the overall organization. While this is the most expensive approach, it ensures a 0% pay gap outcome.

Wrap-Up

A comprehensive, thoughtful pay equity analysis and remediation plan provider must make sure that the organizations they work with have a solid understanding of the options at their disposal and the implications of any approach or combination of approaches.

Remediation plans also have important technical and strategic considerations that we didn’t explored in this article. In our next article, we’ll dive deeper into the more delicate technical aspects of remediation plans.

For now, we want to emphasize that remediation of pay disparities is not a once-and-done process. New talent comes aboard, individuals leave, employees get promoted, new locations are opened, and M&A or divestitures take place. All of these events alter the state of compensation equity in an enterprise.

Equity Methods has extensive experience delivering ongoing pay equity monitoring and bespoke remediation advisory services to organizations seeking to achieve competitive and equitable compensation. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

[1] The relevant sub-groups, or cohorts, are selected according to job architecture in the organization and minimal requirements for the estimation of a regression model. Cohorts with few employees and many relevant pay factors to consider will require different methods of pay equity estimation.

[2] There’s been a lot of talk about moving toward skills-based job and compensation frameworks. While these frameworks would purport to track qualities that traditionally haven’t been measured and archived in human resources information systems, there’s a long way to go.